Trending

The billion-dollar bankroller

The Children’s Investment Fund is writing $1B checks to NYC’s biggest developers, but its money doesn’t come cheap

On a Thursday morning in March 2013, Silverstein Properties’ Marty Burger was trying to keep his cool. His meeting with three major banks to negotiate the terms of a $670 million construction loan for 30 Park Place was nearing four hours, and the parties had reached only the fourth page of a 30-page term sheet.

The meeting went unfinished, and Burger left fatigued and frustrated. Hours later, he received an unexpected proposal from an English financier, Martin Fräss-Ehrfeld: “He said, ‘I can provide the whole loan,’” Burger recalled in an interview last month.

Fräss-Ehrfeld’s firm, TCI Fund Management, or as it is better known, the Children’s Investment Fund, wanted to issue the entire loan as a single lender. A term sheet was written the following day by the fund’s attorneys at the white-shoe law firm Fried Frank, and the deal was signed Sunday — three days after the initial phone call.

“There was no other lender who was going to take that type of exposure by themselves. I was shocked,” Burger said. “The bank, from a regulatory perspective, would never be able to get that done.”

Silverstein Properties, as well as a handful of other New York City heavyweight developers, has turned to the Children’s Investment Fund since it entered the market here in 2011. The U.K.-based hedge fund has taken on a unique role: It writes big checks without syndication. In exchange, borrowers pay a premium for the convenience of dealing with a single lender.

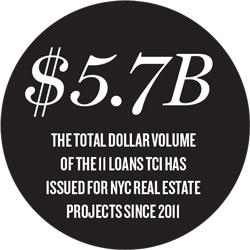

Since issuing its first loan to Macklowe Properties and CIM Group for the Upper East Side conversion of 737 Park Avenue to a condo, the lender has provided $5.7 billion in loans for 11 projects in New York, according to an analysis by The Real Deal.

The firm’s robust financial backing comes partly from multiple U.S. fundraising rounds directed at real estate in recent years. In April, the firm, which has offices in London and New York, raised $1.33 billion from 36 anonymous investors under a fund named TCI Real Estate Partners Fund III LP, according to filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

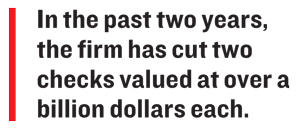

Its aggressive approach has taken developers by surprise — and quietly made it one of the largest lenders in the city. In the past two years, the firm has cut two checks valued at over a billion dollars each, one for $1.25 billion to HFZ Capital Group for its under-construction two-tower condo project 76 Eleventh Avenue, the other for $1.2 billion to the Related Companies and Oxford Properties Group for their mixed-used condo tower 35 Hudson Yards.

“There aren’t that many traditional lenders that can write a check that big without having to syndicate the loan,” said David Eyzenberg, head of New York-based investment bank Eyzenberg & Company.

Eyzenberg said he could not recall another non-syndicated New York real estate loan valued at over a billion dollars, adding that similar loans rarely exceed $150 million.

The price of a loan

TCI’s bold lending has been met by other non-traditional lenders, who’ve rushed in to fill the lending void since the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act forced banks to scale back on large loans.

Non-bank lenders now hold 10 percent market share — up from 2 percent in 2014, according to real estate research firm Green Street Advisors. Last year, non-banks issued almost $60 billion in real estate loans in the U.S. — a 40 percent increase from 2014.

But these non-bank lenders operate under less regulation, largely because they’re not holding deposits from everyday consumers. While TCI’s U.S. funds are regulated by the SEC, the majority of the firm’s assets are in the U.K. and fall outside of the purview of U.S. regulators.

In recent years, JPMorgan Chase has emerged as a competitor to TCI for large real estate loans in the New York area. The bank shifted its riskier construction loans from its commercial lending arm to the investment banking side, allowing it to cushion greater risk. Last year, for example, it agreed to lend Gary Barnett’s Extell Development $900 million for the construction of Central Park Tower.

Other non-traditional lenders, such as Madison Realty Capital, which has closed $7 billion of real estate debt and equity transactions since 2004, issue non-syndicated loans that rarely exceed $150 million.

| DEVELOPER | PROPERTY | LOAN AMOUNT |

|---|---|---|

| HFZ Capital Group | 76 Eleventh Ave. | $1.25 billion |

| Related Companies | 35 Hudson Yards | $1.2 billion |

| Related Companies | 15 Hudson Yards | $850 million |

| Silverstein Properties | 30 Park Place | $660 million |

| Zeckendorf Development | 520 Park Ave. | $450 million |

| Macklowe Properties/CIM Group | 432 Park Ave. | $400 million |

| Ceruzzi Holdings | 151 East 86th St. | $290 million |

| Ian Schrager | 160 Leroy St. | $265 million |

| Macklowe Properties/CIM Group | 737 Park Ave. | $250 million |

| Related Companies | 511 West 18th St. | $125 million |

| Property Markets Group | 10 Sullivan St. | $95 million |

While the flurry of TCI’s recent deals in New York has generated buzz within real estate circles, the firm has remained intensely private.

Its loans are provided under an affiliated Irish subsidiary, Talos Capital, and TCI’s no-frills website offers zero information on its real estate developments. Fried Frank’s Michael Barker, who represents the firm, said the company would not comment for this story.

What is clear, however, is that TCI has taken an unusual path from its origins as a philanthropic venture. The firm was founded in 2004 by British activist investor Sir Christopher Hohn, who set up a parallel charity, Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, which was managed by his wife, and received a total $4 billion endowment.

The fund, which is worth more than $20 billion today, has since steered away from the charity component.

An activist attitude

Hohn, as the story goes, is the son of a Jamaican car mechanic who emigrated to Britain. He was raised in the U.K. and attended Southampton University there before earning his MBA from Harvard Business School, where he met his future wife, Jamie Cooper, at a dinner party.

After a decade working for London and New York hedge funds — including a stint with Richard Perry’s Perry Capital LLC — Hohn launched Children’s Investment Master Fund with $500 million in 2004.

Hohn became known as an activist investor and philanthropist, but also as an aggressive financier who demanded high performance from the companies he backed. His investors — which included the Carnegie Corp. of New York and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology — signed onto peculiar agreements, which not only locked them in for up to five years, but also diverted a third of their investments to the firm’s charity.

Between 2004 and 2008, Hohn’s fund earned a massive 42 percent return on an annualized basis, according to the Wall Street Journal. But that largely unraveled during the global financial crisis, which spurred losses of more than 40 percent.

After Hohn restored wealth to his investors and turned the fund into the world’s largest activist investment vehicle, he and Cooper filed for divorce in 2011 — the same year the firm began issuing loans in New York real estate. Together, the pair were worth more than $1.4 billion, and the divorce became the most expensive settlement ever seen in the U.K. when Cooper was awarded $500 million.

As their relationship dissolved, so too did the hedge fund’s charitable ambitions. Since 2014, the firm has not been required to contribute to the children’s charity, but reportedly makes contributions on a discretionary basis.

Hohn — whose net worth was recently pegged at $3 billion by Forbes — returned to activist investing and through TCI bought large stakes in Australian railway company QR National, Japan Tobacco and News Corp. Today, the fund also maintains large stakes in telecommunications company Charter Communications, European plane manufacturer Airbus and global agricultural firm Syngenta.

And the firm has continued a drumbeat of investment in New York real estate. Its most recent loan came in December, when it agreed to lend Related $125 million for the High Line development at 511 West 18th Street, according to public records reviewed by TRD.

The risk factor

While the Hohns’ divorce and the scuttling of the fund’s charitable mission is well documented, little is known about the firm’s New York real estate investments, and Martin Fräss-Ehrfeld — the man who spearheads the operation here.

Fräss-Ehrfeld has granted few interviews in recent years and is largely quoted only in press statements. In 2011, however, shortly after closing TCI’s loan for Macklowe’s 737 Park, he told TRD that his firm had been searching for a deal for 12 months. And he let slip a small insight, noting that he doesn’t mind if the business plan on a development takes awhile. “The important thing is the underlying asset is still worth a lot,” he noted.

Brokers and developers who have worked with Fräss-Ehrfeld — a former Blackstone Group principal and Merrill Lynch investment banking analyst who joined TCI in August 2009 — paint a picture of a pragmatic (albeit aggressive) operator who is not afraid to commit to a half-billion-dollar deal in days. Perhaps even more than being attracted by TCI’s speed, developers seem to favor working with a single lender — and avoiding the headache that comes with syndication.

“He’s got a unique model: Write large loans,” said Newmark Knight Frank’s Dustin Stolly, a vice chairman of capital markets debt and structured finance. “That’s their differentiating factor; only a handful [of non-traditional lenders] can do $500 million plus checks.”

Stolly, who brokered the $450 million loan for Zeckendorf Development’s 520 Park Avenue in 2014, said the deal turned around in “a matter of days.”

The same no-nonsense approach was taken with the loan for Silverstein’s 30 Park Place, which ultimately clocked in at $660 million. Burger said he was juggling more than a dozen senior and junior lenders for the project when Fräss-Ehrfeld called.

“To get reallocated, you have to get a whole bank group together — it’s a pain in the ass,” Burger said. “And to get Martin there, it was very easy.”

Burger noted that the convenience came at a price. He said he paid 150 basis points more, on a weighted average, above what he would be charged by a traditional bank lender.

Another broker said the firm is known to charge close to 10 percent in interest for construction loans before fees — the high end for non-bank lenders. TCI’s minimum loan bracket is out of reach for many developers in the city. Eyzenberg said his firm had approached TCI seeking $100 million construction loans, but was rejected. “You see the deals they write for Larry Silverstein and Related — those are big deals,” Eyzenberg said. “We’ve shown him a couple of deals, and they’ve all been too small.”

The question now is: Are these giant loans saddling the fund with too much risk? What happens, for example, if one of its borrowers defaults?

“One of the big risks with construction projects is that the developer will slip and fall,” said Manhattan-based real estate attorney Josh Stein.

But, he added, “You have people making investments; why can’t they make investments that are risky?”

Working with the biggest and most reputable developers in the business offers something of a hedge, Stein said. And TCI is undoubtedly calculating that these veteran firms will successfully see their projects through.

“One thing that’s interesting is that they are not afraid to step in and take over the project, unlike banks,” Stein said.