Trending

Reassessing REBNY

<i>As annual dues loom, </i>The Real Deal <i>looks at the group’s finances and whether real estate pros think they are getting their money’s worth for their membership</i>

REBNY head Steven SpinolaThe more than 12,000 members of the Real Estate Board of New York will soon be reaching for their checkbooks to send their annual dues to the influential trade group. And there’s no doubt many will be engaging in a yearly cost-benefit analysis of the nonprofit’s value.

Members pay more than $6 million per year in dues — which are supposed to be in on Jan. 1 — and the group takes in several million more through its annual gala and other income that make up its approximately $9 million annual budget.

The 115-year-old organization is the undisputed top real estate organization in the city, and presents a powerful and unified public front. But there are rumblings of discontent, partly because it operates with a lopsided distribution of power. For example, building owners and residential firms are contributing roughly the same amount of money to the organization, but owners outnumber residential brokers on the board 10 to 1.

This month, The Real Deal takes a look at REBNY as the nonprofit business enterprise it is. We also spoke extensively to real estate professionals to get their take on what the organization is getting right and wrong.

Under the leadership of its president, Steven Spinola, who has been at the helm for 25 years, REBNY pumped up its revenue sharply during the boom years, at the same time expanding its services through its NY1Residential.com listing service as it has faced more competition from websites like StreetEasy and PropertyShark.

And, as The Real Deal reported last month, the organization is increasing its dues for the first time in four years.

The group, led by Spinola and a board of the industry’s top building owners and brokers, holds enormous sway in Albany and New York City when it comes to real estate policy. But some critics — both members and nonmembers — say it favors the large owners, developers and several of the bigger brokerage firms when it comes to the competing interests among its members.

“One of [REBNY’s] main goals is to lobby for the real estate industry,” said one member who criticized the group for not assisting everyone equally. “I think it is most beneficial for developers first, typically. Then commercial firms next, and residential firms last.”

Yet while some members are critical of REBNY’s approach, many brokerages convince most of their agents to pony up their dues each year.

“REBNY has certain issues that need to be worked out. But net-net, we do examine it each year and we do see a benefit of being a member,” said Lawrence Link, president of residential brokerage Level Group.

On the lobbying front, the group has logged successes, like blocking a proposed commercial rent increase cap, and retaining provisions of the luxury and vacancy decontrol laws covering rent-regulated apartment buildings. And the group touts the guidance it provides to members in complex matters such as zoning, building codes and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac regulations.

But the nonprofit has also taken some hits, including failing to get a new 421a law enacted to spur new construction, and failing to block the state from raising the rent decontrol threshold to $2,500 from $2,000 — a blow to residential landlords. Meanwhile, residential brokers knock its Residential Listing Service.

The trade group defends its programs and advocacy as balanced between its groups of members.

“REBNY provides all of its members [with] services and information that assist them in their daily business,” said Frank Marino, an outside spokesman for the organization. “[It] is very active in lobbying for building code and tax issues that have an effect on development in New York City and, in turn, the economy.”

And he stressed residential agents are not overlooked.

“The division of staff, program activities, and commitment to manage and invest in the future of the invaluable RLS system reflect the higher expenditures for the residential division over other divisions,” he said.

Healthy balance sheet

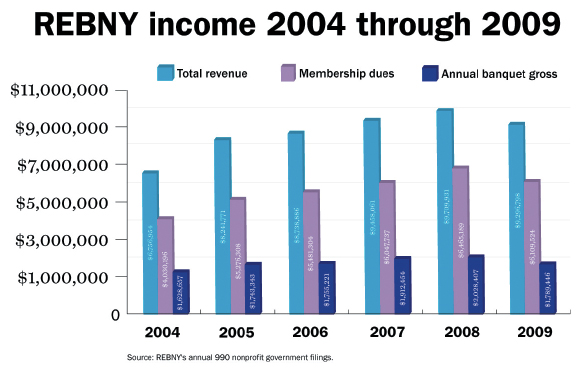

The most recent nonprofit 990 federal filings from the group show that REBNY is in strong financial shape, taking in about $9.3 million in 2009, while spending about $8.3 million that year.

The most recent nonprofit 990 federal filings from the group show that REBNY is in strong financial shape, taking in about $9.3 million in 2009, while spending about $8.3 million that year.

The majority of the revenue comes from members, who in 2009 paid $6.1 million in dues. While down from the 2008 peak of $6.5 million in member dues, the 2009 figure was up by more than 50 percent from 2004, when the group only took in $4 million.

The revenue burst was, in part, due to a large increase in membership and a 6 percent increase in membership fees in 2005, which together bumped up revenues by 31 percent to $5.3 million that year alone.

Meanwhile, for the first time in four years, REBNY has increased dues, this time between 10 percent and 17 percent. The new basic fee for commercial professionals is $550 for an associate broker, and $375 for a salesperson. On the residential side, brokers pay $425 and salespersons pay $275, figures from REBNY’s website show.

While the annual federal return does not break down how much each member firm pays, The Real Deal was able to estimate the total amount that brokers and agents from individual firms pay based on the organization’s fee structure.

According to The Real Deal’s analysis — which was shared with the firms to give them an opportunity to verify the numbers — those at the city’s big residential firms pay the highest fees.

For example, Prudential Douglas Elliman brokers and agents this year will pay an estimated $460,000, compared to the estimated $84,000 paid by those at the city’s largest commercial firm, CBRE Group.

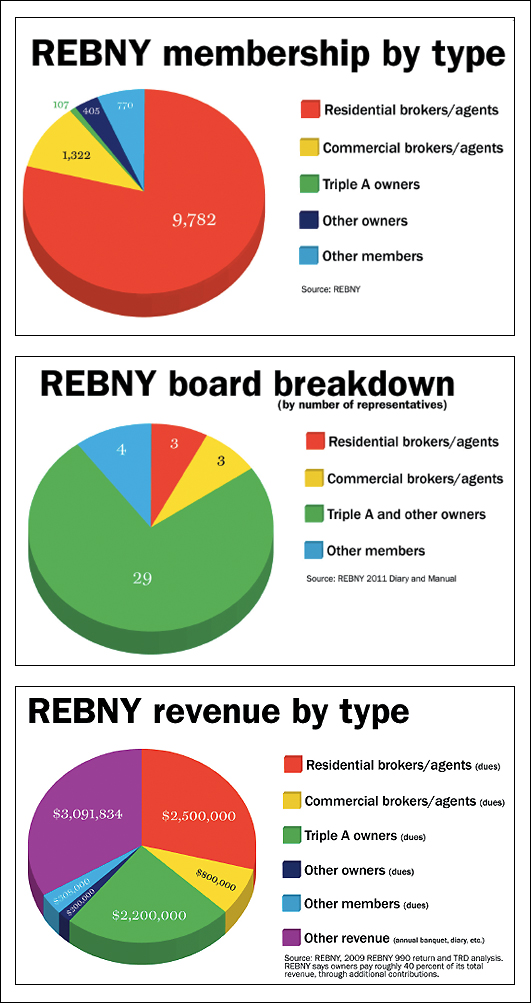

In fact, the residential firms pay about $2.5 million in annual dues, a little under half of the $6 million in member fees, but have scant representation in the organization’s governance.

Indeed, figures from REBNY show that about 78 percent of the membership is comprised of residential agents, yet only three of the 39 board members are residential brokers.

The commercial firms, which according to REBNY have 1,322 member agents, also have three board seats, including one held by the board chairman, CBRE’s Mary Ann Tighe. The law firms, too, are represented by three members. But in a twist, about 512 owners and developers (including 107 so-called Triple A members) hold the lion’s share of control on the board through their 29 board seats.

In response to questions for this article, REBNY initially said that 30 percent of the membership was owners and builders, and that those members provided 40 percent of the annual revenue. In fact, owners and builders only represent about 4 percent of membership, which was revealed in figures provided by REBNY on further analysis after presented with The Real Deal’s estimates.

What’s less clear is what the city’s largest commercial owners pay annually, although it is significant. There are 107 of the largest owners, such as Rudin Management and SL Green Realty, which pay the top “Triple A” rate, $25,000, yielding $2.2 million. That fee applies to owners with more than $40 million in assessed property value. In addition to that, those firms pay a nominal amount for a handful of employees who are members.

But REBNY argues — and the overall revenue numbers bear it out — that owners and commercial firms don’t get off so easy. They pay hefty additional expenses, including for tables at the annual banquet and for other projects, Marino said.

“The owners and builders division is solicited throughout the year, every year, for additional contributions for special activities that would include, but not be limited to, studies, space renovations and lawsuits,” Marino said.

Expense side of the ledger

In 2009, about half of REBNY’s $8.3 million in expenses was allocated to salaries for the staff, and more than $900,000 was spent on renting about 24,000 square feet on a long-term lease at 570 Lexington Avenue. Other expenses included the annual banquet (which in recent years cost about $450,000 and has netted more than $1.3 million), expenses for the group’s frequent brokerage meetings, and lobbying costs.

In 2009, about half of REBNY’s $8.3 million in expenses was allocated to salaries for the staff, and more than $900,000 was spent on renting about 24,000 square feet on a long-term lease at 570 Lexington Avenue. Other expenses included the annual banquet (which in recent years cost about $450,000 and has netted more than $1.3 million), expenses for the group’s frequent brokerage meetings, and lobbying costs.

The firm, which in 2011 had 37 people on staff, has scaled back its costs in recent years, including by cutting salaries.

Spinola’s annual salary in 2009 was $661,380, which was down from the $682,383 he took home in 2006. A review of other, similar trade groups showed that his salary is within the standard range.

For instance, Joseph Strasburg, president of the Rent Stabilization Association, made virtually the same amount, $666,644, in 2009. Other leaders of local private industry trade groups made less, such as the president of the Hotel Association of New York City, Joseph Spinnato, who took home $471,044 in salary and benefits in 2009.

Yet some considered Spinola’s salary and benefits to be high.

“It’s a hell of a lot of money,” one company executive said.

Worth the dues?

It’s no secret that real estate professionals have a wide range of opinions about REBNY.

In the commercial world, leasing agents as a class seemed to have a more positive view of REBNY than investment sales brokers. But the mirror image seems to be true on the residential side, where sales agents seem to have more positive feelings about REBNY than rental agents, insiders said.

Bertram Rosenblatt, a leasing broker at the small Manhattan commercial firm Vicus Partners, said that through REBNY-sponsored leasing market meetings, he obtained comparable leases shared by other brokers and firms like Tishman Speyer and SL Green Realty. In addition, he said he formed other relationships through REBNY that have boosted his business.

On the residential side, a review of the four largest firms showed virtually full REBNY membership. But a few executives at mid-tier firms complained that some competitors don’t require all of their agents to be REBNY members. They charge that those agents who are not REBNY members are getting a free ride to REBNY’s Residential Listing Service.

Part of the reason these firms want their agents to be members, sources said, is to get the REBNY logo — which is like a Good Housekeeping stamp for consumers — on their website.

“[Membership] gives you credibility with the clients, and it gives you credibility with the brokers,” said Khashy Eyn, CEO of residential brokerage Platinum Properties.

And it appears that at several of the city’s biggest commercial firms, not everyone is a member. For example, recent REBNY diaries show CBRE with only about 180 members, but the firm has more than 350 brokers and agents in New York City, the state Department of State website shows. Likewise, Jones Lang LaSalle, with about 45 members in the 2011 diary, shows about 180 brokers and agents in the state database. But a company spokesman said the firm has recently pushed membership up to 75 percent.

This, even as REBNY maintains that “CBRE, like Prudential, has full REBNY membership of all their agents.”

Looking forward

Now, with REBNY seeking higher dues from members, some are reevaluating what they are getting in return.

Some firms that have resisted joining now feel that they need to be a part of the group. One executive at a large commercial investment firm said he would be joining this year for the first time, even as he viewed the fee of more than $20,000 as hefty.

But investment sales broker Timour Shafran, at Capin & Associates, has never been a member and said he doesn’t feel like he’s missing anything.

“I think [REBNY] caters mostly to either owners — larger owners — or leasing brokerage firms,” Shafran said. “I have not found anything that they do that I need.”