Trending

A nationwide sublease surge

When R/GA moved its New York headquarters to Brookfield Property Partners’ 5 Manhattan West, some praised the global advertising agency for adopting state-of-the art technologies entirely controlled by apps.

The new 173,000-square-foot office was designed to attract the best talent, competing with tech firms such as Twitter and Facebook, Bob Greenberg, the company’s founder, told Forbes in 2016.

A few months after Covid-19 hit nearly every industry, however, the Interpublic Group subsidiary was forced to practice its own marketing mantra: “transformation at speed.”

In July, R/GA listed a 65 percent chunk of its office at Brookfield’s West 33rd Street building for subleasing.

“Our primary reason for subletting our office space is agility,” Wes Harris,

R/GA’s global chief operating officer, told The Real Deal by email. He also acknowledged that the agency had to make “difficult decisions” for the rest of the year.

R/GA’s New York base is among the millions of square feet of office space nationwide that began flooding sublease markets across major cities in recent months.

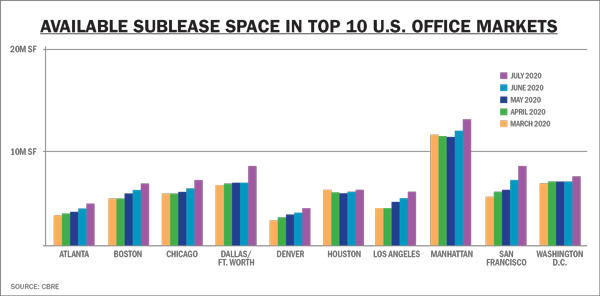

While Manhattan’s office market saw a 2 percent uptick in subleased space in June over March, that rate jumped to 12 percent in July — bringing the total amount of space to 12.3 million square feet, according to CBRE. In Chicago, the amount of subleased space rose from 8 percent to 24 percent in the same period. And in Los Angeles, the rates were 28 percent and 42 percent, respectively.

Many of the initial listings came from technology, advertising, media and information companies. And as the pandemic continues, other business sectors are also looking to trim their real estate footprints.

If the share of sublease space is less than 20 percent of the total available space, the market is considered to be tight.

But as that portion grows, as it has in recent months, it has a negative effect on pricing, since subleased space is often heavily discounted from what the leaseholder pays — in some cases by more than half the price. That’s especially the case when the lease term gets closer to the end, said Michael Colacino, president of the digital advisory firm SquareFoot and former president of the global commercial brokerage Savills.

A recent sublease deal at 245 Park Avenue, for example, went for $25 per square foot — about 70 percent less than the building’s average price — for the remaining two years of the lease, according to sources. The landlord, China’s HNA Group, did not return a request for comment.

“A glut of sublease space is very bad for landlords because it puts enormous price pressure on the direct space,” Colacino said.

“If you’ve got a space subleasing for half the price,” he added, “it’s very tough to go against that as a direct landlord.”

Nationwide spikes

An uptick of subleased space was initially seen in metro markets with heavy concentrations of tech companies, including parts of San Francisco, Austin, Chicago and Boston, said Ian Anderson, CBRE’s director of research and analysis.

Near Chicago’s Financial District, Toast, a cloud-based restaurant software provider, is trying to unload half of its 50,000-square-foot office at 515 North State Street. The company, headquartered in Boston, signed a lease for the space in January — just several weeks before the pandemic hit the U.S.

In April, Toast notified the state of Illinois about its plan to lay off about 120 people. It’s unclear how many staffers were left in Chicago, but according to media reports, Toast cut about 1,300 employees company-wide, half of its workforce. Toast and its landlord in Chicago, Beacon Capital Partners, did not respond to requests for comments.

And in Pasadena, California, the advertising tech company OpenX has listed its 41,000-square-foot headquarters with an outdoor terrace for subleasing, according to LoopNet.com. The company has also reportedly furloughed or laid off employees due to recent revenue losses, though no recent layoff notices were found on the state’s website. OpenX and landlord IDS Real Estate Group, which co-developed the 235,000-square-foot postmodern building, did not return requests for comment.

The subleasing trend wasn’t visible in larger office markets like Manhattan and Washington, D.C., until June. But things started to change as of July, Anderson noted.

“Perhaps as places like Manhattan and Washington begin to get the virus a little bit more under control … they realized this is going to be a little bit of a longer ride,” he said, adding that he and his team are starting to see “more sublease space coming to the market now.”

In Manhattan’s office market, the total share of subleased space is likely to reach 30 percent by the year’s end, if not sooner, said Danny Mangru, Savills’ research director for the tri-state area.

He added that the increase in subleasing led by the TAMI sector is now being followed by financial services and retailers.

A chunk of sublease listings is coming from companies that had rented extra space to accommodate their future growth, said Aaron Jodka, managing director of research and client services at Colliers International in Boston. Facing the downturn, those companies are now taking steps to shed their extra square footage.

“If you think of the overall market conditions prior to the second quarter … most of these markets were at very low vacancy rates,” Jodka said. “Rents were rising, and it was really challenging to find space. So, in order to protect your growth, sometimes you had to lease ahead of schedule.”

Glassdoor is one example.

The California-based employer review website had been rapidly expanding in downtown Chicago in recent years. The company opened a 52,000-square-foot office in 2017 and then signed an additional lease last year to double its space with a goal of hiring 500 new employees, according to the Chicago Tribune.

But the pandemic forced Glassdoor to halt its expansion plans and lay off nearly 200 employees in May. Half of the company’s office space is now listed for subleasing.

“We are reevaluating our office space while our employees work from home due to Covid-19,” said Tyler Murphy, a Glassdoor spokesperson, who declined to disclose the number of employees left in Chicago after the recent layoffs.

Landlord views

A spike in subleasing is part of real estate and other business cycles, and Manhattan’s office market has always bounced back from downturns in the past, said veteran office landlord Bill Rudin, CEO and co-chair of Rudin Management.

“Throughout every business cycle, there’s always companies who have lost businesses, laying off people or giving up space,” he said, noting that landlords generally prefer direct long-term leases but are willing to work with tenants to come up with solutions.

“It all depends,” Rudin added.

RXR Realty CEO Scott Rechler echoed that sentiment.

Rechler said that even though RXR’s office portfolio has yet to have a major tenant list space, a spike in subleasing during an economic downturn is expected as tenants need to address their financial difficulties.

As businesses figure out their finances for 2021, more space could hit the sublease market, he said.

“I don’t think we have a good clarity as to what the long-term prospects are,” Rechler said.

The share of subleases in total office availability recently exceeded 25 percent, an inflection point where the market begins to experience a glut, said Mike Slattery, a research manager at CBRE who covers Manhattan’s office market.

Scaling back is certainly on the minds of most corporate leaders, a recent survey published in KPMG International’s “2020 CEO Outlook: Covid-19 Special Edition” shows. Out of 315 CEOs around the globe who answered the survey, nearly 70 percent checked the box labeled: “We will be downsizing office space.”

The subleasing trend in major cities is likely to continue, as many business leaders who had focused on managing the health crisis are finally looking into their space needs, said Eric Maribojoc, executive director of the George Mason University Center for Real Estate Entrepreneurship.

“Companies are making decisions about the prospects for the economy in the next year or two, and whether they need to scale back,” Maribojoc said.

“Those decisions are being made now, as people look at their budgets for the next year, 2021, and forecasting for 2022, and that’s where you’re going to see that traditional sublease decisions being made,” he added.

The big squeeze

And as more tenants pursue sublease deals, a growing number of landlords are being put in a tough position, regardless of cycles.

“Would they rather have a tenant go bankrupt and reject their lease in bankruptcy? Or would they rather help the tenant survive by subleasing and then have a new tenant that comes in and takes their place and be more financially viable?” SquareFoot’s Colacino said. “It’s a very difficult decision.”

The winner in this scenario is clear: prospective subtenants.

“Subleases are going to become much more desirable in the next go-around because of the realm of the differences in their terms,” Colacino said. “You can find a one-month sublease, a six-month sublease, a one-year sublease or a three-year sublease.”

One of the companies that recently took advantage of subleasing is BigID, a data protection and privacy startup that has outgrown its 5,000-square-foot office in Soho.

A few weeks before the lockdown, the firm signed a lease to take a 21,500-square-foot sublease at SL Green Realty’s 641 Sixth Avenue, a couple of blocks from the Flatiron Building; it plans to move in this fall. SL Green did not respond to a request for comment.

The five-year sublease for the large one-floor space was attractive to the growing firm because of its economics and the timing, said Scott Casey, BigID’s chief operating officer, who declined to disclose the rent for the space.

“We’re going to need this for a few years, and as we continue to grow, we will evaluate a new space at some point,” he said. “And it’s ready to move in, which is great.”

Pricing pressures

As of early September, the average asking rent for a Manhattan sublease was about $63.93 per square foot, about 25 percent lower than the average rent for direct space, CBRE’s Slattery said.

And there’s plenty of sublease space to go around. In August, about 1.6 million square feet hit Manhattan, while 400,000 square feet were absorbed, leaving more than 13 million square feet of available sublease space in the country’s most expensive office market, according to CBRE’s data.

With the abundance of sublease options, the price gap between the two types of space would eventually bring down the average rent for direct leasing options, said Marisha Clinton, Avison Young’s senior director of research for the tri-state area.

During the Great Recession, when the total amount of subleased space in Manhattan grew from 6.3 million square feet in 2007 to 10 million square feet in 2009, the average asking rent for direct space declined by 24 percent over the same period, Clinton noted.

“Keep in mind, it took about nine quarters for that to do so,” Clinton said. “So, things don’t happen overnight. There is at least two years or so before we see any major impact.”

Having too much sublease availability in a certain building, however, could have a significant impact on the pricing, as it may give existing tenants leverage to renegotiate their leases with their landlords, said Lonnie Hendry, a commercial real estate expert with Trepp.

The lowered rent income would affect landlords who are due for refinancing their mortgages in the next 12 months.

“It doesn’t negate their ability to refinance, but generally speaking, it would probably render the property with a lower appraised value because of the cash flow being reduced, and then that lower appraised value would lower the amount of financing that the borrower could take out,” Hendry said.

Remote control

One of the wild cards for office landlords in the current economic downturn is the impact of remote working, which gained momentum out of necessity during the lockdown.

A growing number of public and private companies, including Twitter, Facebook, Zillow Group and Shopify, have announced long-term work-from-home plans.

While Facebook is expanding its Manhattan office footprint with its recent lease at Vornado’s Farley Post Office redevelopment, Zillow recently listed nearly 80 percent of StreetEasy’s 130,000-square-foot digs at 1250 Broadway for subleasing.

The move followed a blog post in late July by Dan Spaulding, the online listing giant’s chief people officer, who noted that about 90 percent of Zillow’s employees can work from home — even after the pandemic.

Zillow signed the 10-year lease for the NoMad office in October 2018 to expand its footprint in New York. The building’s landlord, Global Holdings, did not respond to a request for comment.

“We’re informally exploring what options we have to rightsize our office space in the city,” a Zillow spokesperson told TRD. “While no decisions have been made, Zillow will continue to have a physical presence in New York City.”

R/GA, which has decided to scale back its office footprint for the time being, still values “physical space to connect, be together, work with clients and create headspace,” said Harris, the company’s global chief operating officer.

“We also plan to experiment with smaller satellite offices in New York closer to where our people live, as part of a more decentralized office model.”