Trending

A taxing endeavor

Several real estate heavyweights are backing a push to scrap the city’s property tax system, but it’s a sharp double-edged sword

The NYC Finance Department’s top deputy commissioner told a group of Albany legislators early last year that the city’s property tax — its largest single revenue generator — is a “broken” system. Testifying during a state Assembly hearing, Michael Hyman called it a “winners and losers equation” and noted, “the losers will not be shy about expressing their opinions.”

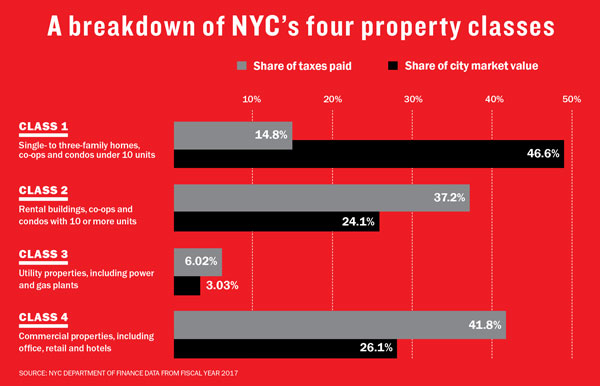

The main problem, he said, is an outdated formula imposed by the state that fuels major inequities tied to property class and location. Among the disparities, luxury condos and co-ops are taxed at a lower rate than moderately priced ones. At the same time, rental properties carry a larger portion of the tax burden than single-family homes.

But while city and state lawmakers have largely avoided the issue since Albany rewrote the tax code in 1981, a recent push to change the status quo could potentially force their hands. Some of New York’s top developers, including the Durst Organization, Related Companies, RXR Realty and Silverstein Properties, are throwing their weight behind Tax Equity Now New York — a reform coalition whose diverse supporters also include public policy think tanks and social justice groups like the NAACP.

The group filed a lawsuit against the city and state in April, claiming the property tax code violates 14 state and federal laws. And the legal challenge seeks to blow up the system without offering a clear solution on how to put it back together.

“Our court papers are pretty agnostic about that,” said Martha Stark, TENNY’s policy director and a former Finance Department commissioner who’s often cited as the person with the most comprehensive knowledge of the city’s tax system. “More than having a discussion about how we want it fixed … what we want really is for the court to provide some guidance about priorities,” she explained.

But even as lawyers for the city and state Attorney General Eric Schneiderman fight for the case to be tossed, a group of five City Council members recently filed a motion supporting the suit — a sign that the coalition’s efforts could attract more favor in the months ahead.

If the case moves forward, the next stop would be Albany, where the Republican-controlled state Senate would hammer out the details with the Democratic state Assembly.

TENNY’s suit now has all interested parties, even some of property tax reform’s biggest proponents, anxious about what would happen if the effort succeeds.

“The lawsuit is a blunt instrument. It’s not surgical,” said David Lombino, a spokesperson for Two Trees Management, which supports the initiative. “You’re going to break the system, and you don’t know where it’s going to go. And that makes some people uncomfortable. But when you look at the alternatives, it’s the least worst.”

An industry divided

Other real estate players backing the coalition have mixed feelings about changing the status quo, industry sources told The Real Deal. Some argue that TENNY is staying mum about how it would rewrite the property tax code if the lawsuit succeeds largely to avoid a political minefield.

The real estate industry came close to banding together to tackle property taxes during the waning days of the Bloomberg administration, according to several insiders who spoke on the condition of anonymity. At the time, the Real Estate Board of New York came closing to filing a lawsuit against the city.

But those with knowledge of the effort said the group’s upper ranks had second thoughts about suing a mayor largely seen as pro-development and decided to back off. Sources said REBNY even discussed the suit with City Hall and pulled back when the mayor and his colleagues said they would rather not be sued.

But those with knowledge of the effort said the group’s upper ranks had second thoughts about suing a mayor largely seen as pro-development and decided to back off. Sources said REBNY even discussed the suit with City Hall and pulled back when the mayor and his colleagues said they would rather not be sued.

This time around, however, the REBNY members guiding TENNY on its property tax reform efforts are doing so at arm’s length. While those firms, including Durst and Related, publicly support the coalition, they are not listed as plaintiffs in the lawsuit. And they are acting independently of the NYC real estate industry’s biggest trade group.

“We don’t like to sue because litigation doesn’t guarantee you an outcome, and so you need to be very, very careful,” REBNY President John Banks told TRD in a recent interview. But he noted that the suit is “absolutely a thing that we talk about frequently.”

For that reason and others, the reform alliance is a tenuous one, sources say. If the lawsuit is successful, it could pit TENNY’s supporters against one another as they grab for their slice of the pie. “Once you start talking about solutions, that’s when the coalition falls apart,” said one person familiar with the matter on the condition of anonymity.

The winners and losers

While the debate on property taxes has long centered on the political clout held by single-family homeowners, the city’s real estate industry also has plenty at stake — with different firms standing to win or lose depending on their portfolios.

If TENNY’s tax reform efforts prevail, companies with large rental portfolios, such as Silverstein and Two Trees, could see their taxes go up or down at individual properties, and not necessarily in equilibrium. Commercial property owners, meanwhile, stand to benefit, as the lawsuit aims to lower the tax burden carried by office, retail and hotel properties. The group that would potentially take the biggest hit are luxury condo developers.

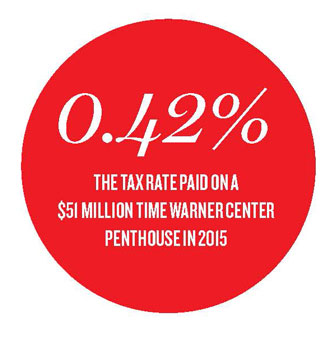

Related, a leading firm in that arena, for example, benefits from one of the biggest gripes about the property tax system: that many high-end condos and co-ops are assessed far below their market value. At the firm’s Time Warner Center, the full-floor penthouse that Russian financier Andrey Vavilov sold to an unidentified buyer for $50.9 million in 2015 receives a roughly 40 percent discount on its tax bill compared to the median tax rate.

For taxation purposes, the city determined the “market value” of the TWC penthouse to be $3.8 million in 2015, and the annual tax bill for the unit that year was $212,504 — 0.42 percent of the purchase price. By comparison, the median effective tax rate for condos across the city in 2015 was 0.68 percent for buildings with 10 or more units, per the city’s Independent Budget Office.

If TENNY’s lawsuit is successful, Related’s luxury condos would likely become more expensive to own. A spokesperson for the firm declined to comment.

“Everyone always assumes that real estate is one giant, tightly organized machine,” said Lombino of Two Trees. “But a rental developer’s interests are very different from a condo developer’s interests, which are very different from a commercial developer’s interests.

“We have both multifamily and commercial,” he added. “And we have no idea where it’s going to end up. Probably some of our properties will be taxed higher and some properties will be taxed lower.”

Going to bat

The two people spearheading TENNY’s legal battle are Stark and Jonathan Lippman — a partner at Latham & Watkins and former head of the state appeals court. Latham & Watkins, which ranked as the world’s highest-grossing law firm in 2017, is representing the coalition in its lawsuit.

Stark had done research on property taxes during the late stages of Bloomberg’s third and final term, before REBNY abandoned its plans to sue the city. But sources said Douglas Durst was one of the key figures who led the trade group’s effort years ago, and that he has played an instrumental role this time around.

“It’s a collaboration,” said the Durst Organization’s spokesperson, Jordan Barowitz. “We’re happy to play that role.”

But the playing field has changed under Mayor Bill de Blasio, and Durst and his allies are less concerned about antagonizing City Hall this time around.

“I think Douglas has been the leader of this because it’s a hot-button issue and there are [a lot of other] people who don’t want to offend the mayor,” said Jeff Gural, who co-chaired the Property Tax Fairness Coalition with Stephen Green in the early 1990s. That group fought unsuccessfully to change taxes for the city’s Class B office buildings.

The brains behind TENNY have their fingerprints all over the coalition’s supporting groups, including the Black Institute, where Stark is a board member, and the Citizens Housing and Planning Council, where Durst is a board member. But most of the supporting organizations have sat on the sidelines while Stark and Lippman drum up public support and Durst works behind the scenes.

Carol Kellermann, president of the Citizens Budget Commission, said she learned of the lawsuit when Barowitz brought it to her attention. But beyond giving a nod of support to the group, she said, CBC has been mostly hands-off.

“We agreed with the points that they’re making,” she said. “If a lawsuit catalyzes everybody to get their act together to make changes, we endorse the idea. [But] we’re just observers. We’re not participating in the meetings.”

Likewise, none of TENNY’s supporting members are listed as plaintiffs in the case — a point the city highlighted when it filed its motion to dismiss the lawsuit on July 7. City lawyers said the complaint used a legal exception called “organizational standing” and was invalid because there was no proof that TENNY’s members suffered any harm.

When the group responded in court, it only had affidavits of single-family homeowners and one commercial landlord who owns a small building on Third Avenue.

“There is no reason to list individual members in the lawsuit,” a spokesperson for TENNY told TRD by email. “Our members have been very public and [have] spoken at press conferences and in media. The city won’t and can’t defend the system on the merits, so they’re grasping at straws.”

A Pandora’s box?

As the lawsuit works its way through the legal system, Stark and Lippman have been meeting with City Council members and the five borough presidents to gain political backing for their case.

Brooklyn Council Member Jumaane Williams, one of the five city lawmakers in favor of the suit, said he thinks TENNY is taking the right approach by not offering solutions at this stage and instead focusing on identifying the problems. He said his concerns about the motives of the group’s supporters in the NYC real estate industry are outweighed by the need to fix a broken system.

“They’re not altruistic groups, and I know they’re interested in something that benefits their businesses,” Williams told TRD. “But I have to look at things on the merits, and there seems to be a lot.”

Staten Island Borough President James Oddo said he supports the idea of property tax reform but declined to submit an amicus brief supporting the lawsuit due to concerns that his constituents will end up paying more. He argued that any injustices in the city’s property tax system fixed by the lawsuit could ultimately be offset by shifting more of the burden onto single-family homeowners.

“It’s a Hobson’s choice to be stuck between the status quo and the potential of opening a Pandora’s box that might lead to even higher property taxes,” Oddo said. “But that’s where we’re at.”

Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer said she thinks those who are unfairly targeted by the city’s property tax are middle-class co-op and condo owners and renters in multifamily buildings — due to the higher taxes their landlords pay. But she said there are no clear solutions as to how to shift the burden.

“If you have an increase on the commercial side, the next thing you know the small stores are going to see the increase,” she said. “People say push it onto Con Ed, but you know what Con Ed’s going to do? Push it right back onto the consumer. Manhattan can’t be the cash cow.”

Others suggested that there could be potential fixes to the property system that don’t exist in the current framework. A means test, for example, could ensure that middle-class homeowners don’t see

their taxes go up. But no one professed to have the intricate understanding of the laws required to opine on what solutions would fit inside the current rules.

The biggest issue with talking about what reform would look like, sources said, is that few people — aside from Stark — know the intricacies of the city’s property tax well enough to offer up real solutions.

“I think the problem is that a lot of people just don’t understand the system,” said Frank Ricci, director of government affairs for the landlord group the Rent Stabilization Association, which supports TENNY. “So they don’t even know what to push for.”