Trending

Inside the battle for StreetEasy’s soul

Three years after buying the NYC listings portal, Spencer Rascoff’s Zillow is rolling out controversial (but lucrative) programs that have led to all-out war with residential brokers. Is there a resolution in sight?

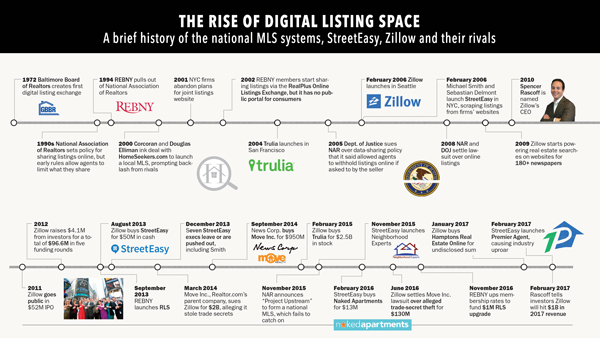

The ink was barely dry on Zillow’s 2014 agreement to buy Trulia for $2.5 billion when the real estate behemoth got its first real challenge — from media titan Rupert Murdoch, no less.

Just 60 days after news broke that the two national residential-listings websites would merge, News Corp. announced its own massive acquisition: The $950 million cash purchase of Move Inc., which operates rival listings site Realtor.com.

At 5:58 a.m. on September 30, the day of News Corp.’s announcement, Zillow CEO Spencer Rascoff came out swinging on Twitter with a two-word reaction: “Game on.”

Reverberations of that tweet are still being felt industrywide thanks to Zillow’s relentless pursuit to dominate the digital-listings space — and to drive value to shareholders.

Game on.

— Spencer Rascoff (@spencerrascoff) September 30, 2014

The company — which launched in 2006 and gives consumers access to residential listings and property information — raked in $850 million in revenue last year, largely by charging real estate agents to advertise on its site.

It wasn’t until 2013, however, when Zillow bought StreetEasy for $50 million, that it entered New York City — the most daunting market in the country.

While StreetEasy had a ubiquitous presence in New York City, with 1.2 million unique monthly visitors and strong name recognition at the time of the deal, Zillow was something of a joke here, unable to figure out how to translate its suburban model to New York’s complex condo and co-op world.

The two companies also had different financial models when they joined forces — with StreetEasy relying on premier subscriptions and general advertising and Zillow selling brokers ads placed directly next to property listings.

Since taking control of StreetEasy, however, Zillow has been reshaping the portal to fit into its own mold — or, as many say, Zillowfying it. But the changes it’s implemented have not come without backlash.

Critics say it’s stripped the site of some popular features that earned it a widespread following. And the company has gradually launched some controversial programs, including Building Experts and Neighborhood Experts, which allow agents to advertise on specific buildings’ pages and be labeled “experts” if they’ve done only two deals at a property or in an area in the previous 36 months.

But its latest program — a lead-generation tool called Premier Agent that the company rolled out on March 1 — has led to all-out war between the brokerage world and the company.

The program, which has been used nationally for some time, directs consumers to agents who advertise rather than the brokers who actually have the listing on a property. The move has prompted a multi-pronged and bruising fight with several key factions in the residential community: agents, who are slamming the program as a bait-and-switch scheme; the Real Estate Board of New York, which is calling on the state to investigate its legality; and brokerage chiefs, who are boycotting it by not reimbursing agents who use it.

But StreetEasy and Zillow are of the take-no-prisoners ilk.

The Seattle-based public company, which describes itself as a media firm in the real estate space, has good reason to push its latest program.

Last year, Premier Agent was a cash cow for the company nationally, generating $604 million, or 71 percent of Zillow Group’s revenue — a 29 percent jump from 2015.

Although Rascoff told investors in 2016 that monetizing StreetEasy has proved “a little more complicated” than anticipated, he’s already seen serious results on the revenue front.

Zillow doesn’t break out StreetEasy’s performance, but the New York business quadrupled its earnings between 2013 and 2016, the CEO said during a February 7 earnings call.

And Zillow is clearly hungry for more, analysts said.

“Zillow is a public company. Their job is to grow revenue and earnings,” said Shyam Patil, a senior analyst at the Susquehanna International Group, a global quantitative trading firm. “If they’re doing something that for them is driving their financial results, they’re going to stick with it even if they get pushback.”

How closely StreetEasy sticks to Zillow’s playbook remains to be seen.

Just before press time, StreetEasy’s top executives — who had been publicly insisting that they wouldn’t roll back the program — began testing several different ways Premier Agent could look on the site, including one version featuring contact information for listing agents.

In an email to agents, Susan Daimler, StreetEasy’s general manager, said improving the site’s design would be an ongoing process. And she invited agents to submit feedback via a newly created email address.

In an email to agents, Susan Daimler, StreetEasy’s general manager, said improving the site’s design would be an ongoing process. And she invited agents to submit feedback via a newly created email address.

“Every market has its challenges,” Daimler told The Real Deal during a phone interview last month, during which she defended the Premier Agent program. “Across the country, in every single market, we strive to have that open dialogue with the industry, and that’s no different here.”

“The strategy for Premier Agent is giving consumers choice about what real estate professionals to contact to get them the fastest response possible,” she said.

However, one brokerage chief said StreetEasy’s apparent willingness to tweak its approach in New York is a strategy to appease a key constituency.

“This program is not going away, but they don’t want to completely antagonize the brokerage community,” the executive said. “They don’t want to be the enemy, so if there’s an area where they can be accommodating, they will.”

Susquehanna’s Patil put it this way: “StreetEasy knows its success depends on brokerages supporting it.”

Legal maneuvering

Zillow is not the only disruptor that’s rocked New York’s residential industry in the last few years. The established brokerage business is also contending with a slew of upstart firms — the most notable being the venture-backed Compass, which has aggressively poached agents —as well as a host of new websites and apps targeting buyers and renters.

These new players have all been challenging the status quo and adopting new ways of buying and selling real estate in the 21st-century internet age.

But the industry’s complicated relationship with StreetEasy dates back all the way to 2006, when the company launched and would scrape listings off firms’ websites to get information the brokerages were reluctant to share. After finally accepting (and even embracing) StreetEasy, the industry ultimately began turning over its listing feeds to the platform.

Now that relationship has been upended.

Just like several firms went after Compass in court for allegedly stealing trade secrets, brokerage executives have mounted a legal defense to try to force Zillow to abandon Premier Agent.

Under pressure from its residential members, REBNY fired off two letters to the New York State Department of State, which oversees brokerage licensing, taking issue with the program.

On March 3, it asked the DOS to investigate whether the program violates state advertising laws, which prohibit agents from marketing another broker’s listing.

“The Premier Agent Program is identical to a real estate agent purchasing a billboard, advertising another firm’s listing on the billboard without identifying that firm,” REBNY’s lawyers argued.

REBNY’s mid-March follow-up letter argued that Premier Agent had caused a “maelstrom of consumer confusion.”

StreetEasy’s lawyers quickly shot back, accusing REBNY of favoring listing agents over buyer-side agents and trying to “suppress competition.”

“Listing agents are, of course, free to remove their advertisements at any time,” StreetEasy attorney Steven Shepard wrote. “They choose not to do so because StreetEasy is a popular and effective way to reach interested buyers.”

He added: “REBNY’s intent is to make it more difficult for interested buyers to find and contact independent buyer-side agents to represent them.”

A DOS spokesman told TRD that the agency is “preparing guidance” on the Premier Agent program, which it will share with licensed agents online.

StreetEasy clearly knew that the industry was not going to sit idly by when it rolled out the program. Executives at the website attempted to blunt the blow in advance, giving major brokerage chiefs a heads-up about the initiative several weeks before officially unveiling it. Those brokerage heads were required to sign nondisclosure agreements.

Halstead Property’s Diane Ramirez, co-chair of REBNY’s residential division, who noted that she usually stays out of the fray, said she was jolted into action after StreetEasy revealed its plans.

Ramirez — who sits on the board of rival Move Inc. — called Premier Agent a “huge shift in focus” and said the program was ripe for consumer misunderstanding.

While Ramirez has a horse in the race given her connection to Move Inc., she is far from the only one speaking out.

Several high-profile brokers have taken a public stand against the new program.

Nest Seekers International’s [TRDataCustom] Ryan Serhant — better known as a co-star of “Million Dollar Listing New York” — posted two videos to his Instagram feed and bashed the program for serving “no other purpose than for StreetEasy to make money.”

In one video, he pulled out his mobile phone and called up a broker who advertised next to one of his exclusive listings, in a ploy to show that the broker was ill-informed about the property.

“There is no vetting process for agents who pay to get into the Premier Agent program other than a credit card number,” he told TRD.

Meanwhile, Stribling & Associates’ Kirk Henckels pulled four listings worth $40 million off StreetEasy — including a co-op at 720 Park Avenue asking $20 million — in response to what he described as its “pay-to-play scheme.” (However, he did not remove all of his listings and the co-op at 720 Park had been on the market a year, a StreetEasy spokesperson noted.)

But not every broker can afford to lose the eyeballs that StreetEasy provides for listings, and some buyer-side brokers say Premier Agent is a good thing.

Kobi Lahav, a managing director at Mdrn., said the program has benefited his buyer-side business and helps consumers by making it less likely that one agent represents both sides of the deal.

“The outcry comes from the listing brokers who think more of themselves and less of their client,” he said. “In a way, [listing brokers] are like taxi drivers who just realized Uber is in town, or the hotel industry that just discovered Airbnb.”

Susan Daimler

Either way, in the long run, the New York brokerage community might not have a legal leg to stand on, some lawyers said.

“I don’t believe there’s any ultimate harm to the consumer. At its core, this is a more a fight over consumer dollars than consumer confusion,” said Manhattan-based real estate attorney Terrence Oved, who is not involved in the case. “The harm is to the listing broker. That’s why it’s become such a cause célèbre, because it impacts their bottom line.”

REBNY attorney Claude Szyfer told TRD the board has no plans to sue Zillow or StreetEasy over Premier Agent.

Still, several firms — including the Corcoran Group, Citi Habitats and Town Residential — are fighting back with their pocketbooks, refusing to reimburse brokers who participate in the program.

It seems unlikely that firms would actually withhold listings from StreetEasy wholesale. Forgoing exposure to potential clients could mean losing out on buyers.

Some blame the industry at large for the current predicament with StreetEasy, pointing to the lack of a consumer-facing Multiple Listing Service (see related story on page 39).

Henry Abramov — former head of research for listings portal On-Line Residential, which is only accessible to brokers — put that responsibility squarely on REBNY’s shoulders. He said its failure to create an MLS left a hole in the market, which StreetEasy swooped in and filled.

“If there was one system that required everyone to participate, you’d have yourself a fully-functioning MLS,” said Abramov, who’s now head of research at Lee & Associates. “The fact that [REBNY] doesn’t require it and have it in place creates an opportunity for StreetEasy to say, ‘Hey, everything is so scattered, they don’t have a consumer-facing website, we’re going to get in.’”

Town CEO Andrew Heiberger agreed that a centralized MLS could unite brokers who are disgusted by StreetEasy’s “pay-to-play” strategy.

“StreetEasy has alienated many members of the brokerage community by using our exclusive listings and client relationships to pad their profits,” he said.

It rhymes with pillow

It’s hard to imagine, but Zillow wasn’t always a household name.

Real estate appraiser Jonathan Miller said that back in 2005, he was at a party hosted by real estate websites Inman and Curbed.com when the founder of Curbed, Lockhart Steele, introduced him to Richard Barton, the founder of the travel website Expedia.

“We chatted for like 15 minutes and he said, ‘We’re launching a firm tomorrow called Zillow,’” Miller recalled. “I said, ‘Zillow?’ And he said, ‘Yeah, rhymes with pillow.’ The next day it exploded.”

Rascoff, a Harvard-educated entrepreneur who grew up in New York and Los Angeles, was there that day — as part of Zillow’s founding team.

After a stint at Goldman Sachs, he co-founded the travel website Hotwire.com in 1999 at age 24 and sold it to Expedia in 2003. A few years later, Barton and his partner Lloyd Frink brought Rascoff on as one of Zillow’s first employees.

In 2010, the baby-faced Rascoff, who declined to comment for this story, was tapped to become CEO, and in 2011 he took the company public.

Zillow’s easy interface and home-valuation tool made the site an instant hit with consumers. “You could now look at your neighbor’s house, your best friend’s house, and see how much it was worth,” Miller said. “It certainly was a tool that was marketed to help you, but really it was for the voyeur.”

As it turned out, there are hundreds of millions of people eager to catch a glimpse of those numbers.

During 2016’s fourth quarter, Zillow attracted 140 million average monthly unique visitors, a 13 percent year-over-year increase. And the company is on track to hit the $1 billion revenue mark this year.

Streeteasy’s office in New York

“Zillow generates a lot of traffic, and in a given zip code, if you’re not on Zillow, you’re missing out on potential home sellers,” said Susquehanna’s Patil, who follows Zillow. “So in a way, agents have to be on the platform.”

But breaking into New York was its own special challenge — particularly because Zillow’s model for valuing properties was more geared toward single-family homes, not urban settings.

So buying StreetEasy was like hitting the jackpot.

“Simply put, StreetEasy has cracked the code in New York,” Rascoff said in a statement at the time.

Sources involved in Zillow-StreetEasy acquisition said the spirit of the agreement was to let StreetEasy keep doing what it was doing best: providing users with detailed listing information, including property histories and price comps as well as data on the market at large.

But that didn’t completely happen. While Zillow made StreetEasy free to consumers, critics have blasted the company for removing tools that allowed users to search recorded sales, sort listings by monthly payment and shop for a broker.

And shortly after Zillow came in, expansion plans were scuttled, which also angered StreetEasy backers. Newly launched portals in South Florida, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia were shut down, and plans to expand to Chicago and Miami were dropped.

After members of StreetEasy’s founding team pushed back against the changes, a half-dozen senior executives left or were pushed out, including founding CEO Michael Smith.

Much to the consternation of the original employees, Daimler — who sold her real estate startup Buyfolio to Zillow in 2012 — was installed at the helm. (Daimler and her husband, Matt, also sold their travel startup, SeatGuru, to Expedia in 2007.)

“She was gifted oversight of a company she had nothing to do with building,” said a former StreetEasy staffer.

Another staffer had this to say: “It was just a matter of months before StreetEasy felt different.”

Today, StreetEasy and Zillow take up three floors at 130 Fifth Avenue, where they have a total of 171 staffers. StreetEasy has roughly 60 of those employees — up from 34 when it was acquired.

The open floor plans at both operations are modeled after Zillow’s offices nationwide, with conference rooms and phone rooms named after local streets and landmarks. The company provides catered lunches on Tuesdays and happy hours every other Thursday. StreetEasy also reimburses staffers for things like Citi Bike memberships and pet insurance.

Despite those Silicon Valley-style perks, there have been tensions between the company’s original employees — particularly among those who’ve left — and the company’s current management.

Daimler, however, disputed the idea that the company fundamentally changed StreetEasy, saying the website is Zillow’s only hyper-local brand and is intentionally tailored to its New York City audience.

Daimler, however, disputed the idea that the company fundamentally changed StreetEasy, saying the website is Zillow’s only hyper-local brand and is intentionally tailored to its New York City audience.

She said Zillow rolled out Premier Agent in New York after refining it in other markets.

“We know New York City is a discerning market with savvy agents and buyers,” she said. “We continue to have open dialogue with brokerages and the industry at large.”

Monopolizing the market

New York is not the only market that has greeted Zillow and its Premier Agent with suspicion.

Some firms and MLS systems across the country have withheld their listings from the website or struck compromises with it.

RealTracs, an MLS in Tennessee, opted to give Zillow truncated listing information. And Austin, Texas-based Keller Williams forged a deal with Zillow — giving the real estate giant access to its listings, but requiring that Keller Williams listing agents be named alongside agents who paid to advertise.

Charlotte, North Carolina-based Allen Tate Realtors, meanwhile, pulled its listings from Zillow and Trulia in 2014 and instead put them on Murdoch’s Realtor.com.

Michael Carucci, an agent in Boston, called Zillow the “bane of our existence” and said Premier Agent is a “bait-and-switch” scheme.

There have been attempts to take Zillow on.

In recent years, the National Association of Realtors, which opposed the Zillow-Trulia merger on antitrust grounds, spearheaded the creation of a national MLS system called Upstream, though that’s failed to gain industrywide traction.

And last year, News Corp.’s digital real estate services generated $229 million in revenue, a 21 percent year-over-year gain, signaling the growing importance of Realtor.com, the marquee brand. (Realtor.com is actually owned by NAR, which sold Murdoch’s Move Inc. the right to operate it.)

Still, Realtor.com has virtually no presence in New York, and Zillow is continuing to expand here.

Last year, Zillow paid $13 million in cash for New York-based rentals site Naked Apartments, and this year it also bought Hamptons Real Estate Online, or HREO, a listings portal on the East End.

Despite any issues New York agents might have, StreetEasy has a virtual monopoly here because it’s been so widely adopted by consumers, said OLR President Jonathan Greenspan, speaking at a “Big Data + Real Estate Forum” hosted by TRD in mid-February.

“Owners won’t let them take listings off,” he said.

But Harley Courts, CEO of startup brokerage Nooklyn, which focuses on rentals in Brooklyn, said the only way for agents and brokerages to retain a competitive edge is to control their own listings. “We don’t want to give away our data set,” Courts said at the same forum. “It’s a big, big, big mistake to give away your data.”

Brown Harris Stevens CEO Hall Willkie conceded that brokers lost control of their listings to StreetEasy, which built an enormously successful audience of buyers, sellers and agents.

“We provide this inventory to StreetEasy,” he lamented. Now, “StreetEasy wants to sell us back the right to put our names on it.”