Trending

Kushner Companies v. Everyone

Opposition from local politicians in New York and New Jersey and ongoing investigations into the family real estate firm are forcing it to step back and rethink its strategy on major development projects

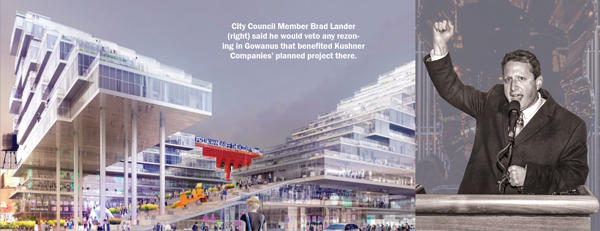

City Council member Brad Lander sat for an interview on public radio last November and ended Kushner Companies’ hopes of building a major mixed-use development in Gowanus, Brooklyn.

The firm, and its partners SL Green Realty and LIVWRK, had bought the 140,000-square-foot site for more than $70 million in 2014. But the success of the project depended on a rezoning of the neighborhood, and that depended on Lander, the local Council member expected to get the final say on a rezoning proposal.

During the radio interview, though, Lander suggested he would veto any rezoning that benefited Kushner Companies.

“Voting to take part in enriching the White House senior adviser while he’s got authority over the canal, that feels ethically tainted in a way I don’t see how I could do and how I could ask my colleagues to do,” he said.

Five months later, Kushner and its partners sold the site at 175-225 3rd Street to RFR Realty for $115 million, almost 60 percent more than they paid for it.

From company founder Charlie Kushner going to prison — and asking his fresh-faced son Jared to take the reins — to the family real estate firm setting a city record with its $1.8 billion 666 Fifth Avenue buy, Kushner Companies has been in the spotlight since the early aughts. But Donald Trump’s White House victory has turned it into one of America’s most politically connected and publicly scrutinized companies.

Now local officials in New York and New Jersey — many of them Democrats opposed to the Trump administration — are forcing the Kushners to make tough decisions on everything from development plans to lender and investor partnerships. These politicians, who play a key role in zoning approvals, tax abatements and housing regulations, increasingly see Kushner Companies as an unwelcome guest.

Meanwhile, Special Counsel Robert Mueller and a handful of federal, state and local agencies have examined the Kushners or their partners in several investigations into the family real estate business. And they have reportedly cast a wide net — looking into everything from the firm’s treatment of tenants to Jared Kushner’s meetings with potential foreign investors after the 2016 presidential election.

No law enforcement agency has brought an indictment against the Kushners, and Charlie Kushner recently said his lawyers were notified that two of the investigations have already been closed.

But sources say it would be highly unusual for the mounting number of inquiries not to take a toll on the company.

“In the normal situation, would I expect it all to magically go away? No.” said Laurie Levenson, a former assistant U.S. attorney and a law professor at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. “You only need one conviction of Kushner to send a very large message.”

Local friction

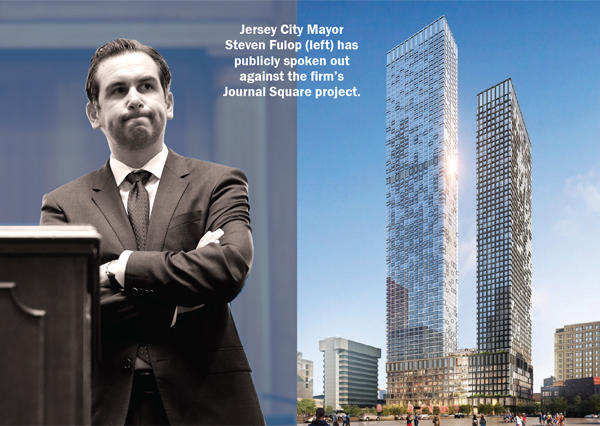

In Gowanus, Kushner Companies was forced to abandon a ground-up development. In Jersey City, it may have to do the same after Mayor Steven Fulop denied tax abatements for its 1 Journal Square luxury towers and declared that the firm is in default of its development agreement with the city.

That has led some, including the firm’s partners, to say Kushner Companies will need to change its strategy and focus on different projects if it wants to continue to grow in greater New York, since political opposition and public scrutiny are unlikely to go away anytime soon.

“While the rules should be the same for all prospective developers, most New York City elected officials are not going to be bending over backwards to help Kushner Companies,” said Dan Garodnick, the former Council member who oversaw the Midtown East rezoning.

“While the rules should be the same for all prospective developers, most New York City elected officials are not going to be bending over backwards to help Kushner Companies,” said Dan Garodnick, the former Council member who oversaw the Midtown East rezoning.

Lander described his decision to oppose the firm’s Gowanus project as a difficult one.

“This was a situation where you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t,” he told The Real Deal in a recent phone interview. “That’s part of the problem of a conflict of interest: There’s not a clear good side to come down on.”

Lander said he supports private development in Gowanus, a key step to revitalizing the neighborhood. But he noted that building a large new property on that site can’t happen unless the federal government cleans up the Gowanus Canal through the Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund program. And as a senior White House adviser, Jared Kushner could potentially steer federal funds toward the Gowanus cleanup, which would directly benefit his family. Alternatively, he could use his influence with the EPA as leverage for concessions from the city — a classic conflict-of-interest situation.

“You fear actions that you could take might put the cleanup at risk,” Lander said, “but you also don’t want the cleanup to be happening for private gain of the decision-makers.”

In a recent sit-down interview at the firm’s 666 Fifth office tower, Charlie Kushner dismissed Lander’s argument about conflicts of interest and accused the Council member of playing politics.

“We think it is discrimination, we think it is unfair,” he said. “But we decided in the best interest with our partner, let’s just move on.”

LIVWRK’s Asher Abehsera, a partner on the Gowanus site, said Lander’s decision and his announcement on public radio felt like the Kushners and their partners were being singled out. “There was an element of ‘don’t even think you have a shot at this anymore’,” he said.

Survival tactics

But while Kushner Companies walked away in Brooklyn, it has been less willing to do so in Jersey City. The firm plans to build two 66-story towers at 1 Journal Square in the city’s center and had initially lined up WeWork as an anchor tenant to carve out space for its WeLive co-living customers.

Then WeWork left the project last year — costing 1 Journal Square a $6.5 million annual state tax credit tied to the co-working company as part of a 2015 state economic development program. Charlie Kushner said his firm decided to ditch WeWork. He called the WeLive communal designs for the property a “bastardized plan” and said “if their concept was wrong, we would have to rebuild the building.” A representative for WeWork declined to comment.

Meanwhile, plans to raise $150 million in construction financing for the planned 744-apartment project through the EB-5 program backfired in May 2017 when a Chinese roadshow advertising the project (and seemingly implying the United States president backed it) caused an uproar and sparked a federal investigation that may still be ongoing. Charlie said the investigation has since been closed. The U.S. Attorney’s office declined to comment, which is its standard practice.

Adding fuel to the fire, Fulop has publicly spoken out against the Journal Square project, describing what he said was “a sense of entitlement” on behalf of the Kushners. In April, the city threatened to block the development, citing a missed deadline to start construction and an unpaid $40,000 municipal fee.

Adding fuel to the fire, Fulop has publicly spoken out against the Journal Square project, describing what he said was “a sense of entitlement” on behalf of the Kushners. In April, the city threatened to block the development, citing a missed deadline to start construction and an unpaid $40,000 municipal fee.

In response, Charlie Kushner called Fulop “another New Jersey asshole politician” and accused the mayor of appealing to “Trump-haters.” As for the unpaid fee, Charlie dismissed it as nonsense. “I’m still not clear what payment we missed,” he said. “If we missed a payment of $40,000, did we get a follow-up letter? … We asked everybody, asked our partner.”

A representative for Fulop’s office, however, shared a letter that was sent to the Kushners in March explaining that the developers had failed to pay the annual administrative fee from 2017 that was a condition of the redevelopment agreement. A follow-up letter sent to Kushner Companies and its partner KABR Group in April shows they had then paid it.

But in that letter, the Jersey City Redevelopment Agency’s acting executive director, Diana Jeffrey, said the agency doubted the developers’ ability to fully fund 1 Journal Square and their ability to “see the Project through to fruition.”’

The following month, Fulop announced that he would not support additional tax abatements for the project, saying the application, as proposed, “doesn’t work for us.”

“We are Front and Main Street,” Charlie Kushner told TRD. “So for them to not want that developed, who does that benefit? The local citizens? … If they force me to own that property for the next 100 years, and my great-grandchildren develop it, it’ll be worth a zillion dollars more.”

Adam Altman, a managing partner at KABR, was more reserved when asked about the dispute between the development partners and local Jersey City officials. “We are working it out,” he said. “We acknowledge we have a disagreement with the mayor. We don’t think it’s constructive to try to resolve our differences in the press.”

On June 27, the Kushners sued Jersey City and its mayor, citing political discrimination.

“It’s not like the Kushners have a great deal of credibility in anything they say,” Fulop said in a statement. “Their entire lawsuit is hearsay nonsense. Bottom line — the same way they illegally use the presidency to make money is the same way here they try to use the presidency to be pretend victims. They will do anything to manipulate a situation.”

Sources close to Kushner Companies say it would make sense for the firm to stick to as-of-right properties in New York and steer clear of anything that requires public approval. Michael Fuchs of RFR Realty, a partner in the firm’s Dumbo office portfolio and the buyer of the Gowanus site, said that while he “can’t speak for Kushner Companies,” it would be wise for the firm to invest in projects that draw less public attention.

Sources close to Kushner Companies say it would make sense for the firm to stick to as-of-right properties in New York and steer clear of anything that requires public approval. Michael Fuchs of RFR Realty, a partner in the firm’s Dumbo office portfolio and the buyer of the Gowanus site, said that while he “can’t speak for Kushner Companies,” it would be wise for the firm to invest in projects that draw less public attention.

“The real estate business is difficult enough, so you don’t need the extra burden of extra scrutiny,” Fuchs said.

In New York, Kushner Companies seems to be paring down its holdings and focusing on fewer and more modest ventures. In addition to the Gowanus sale, the firm sold its minority stake in two massive development sites in Dumbo to its partner CIM Group in June. And last year, it sold its stake in a nearby vacant office building at 175 Pearl Street, as well as its stake in a Dumbo hotel previously owned by the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Meanwhile, the company scrapped plans to tear down 666 Fifth Avenue and replace it with a massive residential and retail tower after being unable to close on enough financing for the plan. Instead, the company is now opting for an office renovation with a new partner, Brookfield Property Partners, whose investment in the building is still pending.

Two Trees Management’s head of external affairs, David Lombino, said Kushner Companies wasn’t known in the past for building complicated projects in New York that require public approval. Not building them in the future wouldn’t pose a significant change, he noted.

“Lots of companies never even touch that public sphere and still make tens of millions of dollars,” he said.

Bank reservations

Kushner Companies has also seen its access to certain lenders significantly change since Trump became president.

In late 2015, a senior executive at a major foreign bank had lunch with Jared Kushner, then the firm’s CEO, and Laurent Morali, its president. The two pitched the banker on helping them finance 666 Fifth, which they were still planning to demolish and replace with the soaring condo and retail skyscraper.

Like numerous other investors approached about the project, the banker — who talked to TRD on the condition that his name and his bank’s country not be mentioned — immediately decided it was too risky financially and rejected the overture.

The banker said he was still open to lending to Kushner Companies on other properties at the time. But since Jared Kushner joined the White House in early 2017, he said, he has made a “conscious decision” not to do business with the Kushner family’s real estate firm.

“For many banks, Kushner Companies is now a PEP — a politically exposed person,” the banker said. “That just requires a lot more explanation internally, a lot more documentation, a lot more [‘know your customer’ work]. For me, it’s not worth the headache.”

An executive at another overseas bank, who also spoke on condition of anonymity, said he too was unwilling to lend to Kushner Companies, citing the public scrutiny on a company so closely tied to the White House. “You might end up in the paper,” that executive said. “Is it worth it? I don’t know. Life’s too short. There’s plenty of deals out there.”

At the same time, Charlie Kushner said he’s nixed sovereign wealth funds and investors tied to foreign governments from the negotiating table, to reduce possible conflicts of interest as long as his son’s work involves foreign policy matters.

Doing so further narrows the pool of potential finance partners. But sources say there are plenty of alternative lenders willing to work with Kushner Companies, and for now the company seems to have no problem getting loans from major financial firms. Last June, for example, Bloomberg reported that the company was struggling to refinance its Jersey City apartment building Trump Bay Street. But in March it landed a $200 million mortgage from Citigroup.

And with the exception of Deutsche Bank — which Charlie Kushner said temporarily stopped issuing mortgages to the firm while the Justice Department was investigating the German financial giant — none of the Kushners’ existing lenders appear to have stopped working with the company.

New York Community Bank, which has issued more loans to the firm than any other bank, according to Real Capital Analytics, said in a statement that it “has enjoyed an excellent lending relationship with the Kushner Companies for over 15 years and we look forward to reviewing new financing opportunities with them in the years ahead.”

Charlie Kushner dismissed the notion that his firm has a harder time landing debt, claiming in May that it was on track to close $2 billion in financing in the first half of 2018.

“Not that there’s not challenges,” he said. “Jersey City is a challenge. It shouldn’t be. Gowanus was a challenge. It shouldn’t be. But generally, our business is plowing ahead like a bulldozer and we just keep moving forward.”

Inquiring minds

On Tuesday mornings at 8:30, Kushner Companies’ executives and key employees meet on the 15th floor of 666 Fifth to discuss the pressing business matters of the day.

Those who have attended the weekly assembly describe the mood as amiable and the agenda as extremely thorough, with no corner of the business left untouched. These days, Charlie Kushner’s daughter, Nicole, is there, while his wife, Seryl, sometimes attends. And family members are known to embrace each other in front of staff.

But in federal court records for Richard Stadtmauer — a convicted former company partner and Charlie Kushner’s brother-in-law — prosecutors painted a less wholesome picture of company gatherings. It was at Tuesday “cash meetings” in 2000, prosecutors alleged, that Charlie Kushner and other executives plotted out how to “lose a bill,” that is, how to deduct personal and other non-business-related expenses from real estate partnerships controlled by Kushner Companies.

Prosecutors in New Jersey alleged that those expenses included consulting fees to help revive the political career of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, private school tuition for children of company executives and the catering of a fundraiser for then-New Jersey Democratic Gov. John Corzine.

In 2004, Charlie Kushner pleaded guilty to 18 counts of tax evasion, illegal campaign contributions and witness tampering; he served 14 months in an Alabama federal penitentiary. Three associates also pleaded guilty to related offenses, with the exception of Stadtmauer, who went to trial and was sentenced to 38 months in jail in 2009.

These days, the inquiries into the Kushner family are scattered across agencies in Washington, D.C., New York, Maryland and Texas. Meanwhile, a handful of Democrats in Congress have called for even more investigations into Jared Kushner. Some have even requested information directly from Kushner Companies.

U.S. attorneys have reportedly probed the firm’s use of the EB-5 visa program and, separately, its relationship with Deutsche Bank. New York state’s Department of Financial Services is also reportedly looking into the Deutsche connection, as well as the firm’s relationship with Signature Bank and New York Community Bank. The focus of that investigation is whether Jared Kushner is personally guaranteeing any outstanding loans in the case of a default, CNN reported.

Mueller, meanwhile, is looking into the senior White House adviser’s attempts to finance 666 Fifth with foreign money during the presidential transition. The Maryland attorney general is investigating Kushner Companies’ use of civil arrest to collect overdue rent. And the list goes on.

Charlie Kushner denied any wrongdoing and said authorities are welcome to pore over his firm’s records. “We’ll give them the papers, so I do not lose one second of sleep,” he said. “You guys think about it, but I don’t.”

But white-collar legal experts who spoke to TRD said the scope of these investigations means the company needs to be taking them seriously and needs to be prepared for all scenarios.

“You have to do an internal investigation. You have to make sure you have internal controls,” said Levenson, the former assistant U.S. attorney. “Very importantly, you have to make sure people are not trying to hide or destroy evidence, because people panic, and the cover-up is often worse than the initial violation.”

Defense mode

Former deputy federal prosecutor and defense attorney Ellen Podgor said organizing legal defenses for disparate inquiries facing the Kushners would come with “enormous difficulty.”

Whether or not it’s been a challenge, Kushner Companies has certainly beefed up its legal team. In addition to its in-house counsel, Emily Wolf, the firm has tapped outside defense attorneys. According to one source, it enlisted Ben Brafman, who is known for representing Dominique Strauss-Kahn, Harvey Weinstein, Martin Shkreli, as well as celebrities and other real estate moguls.

And to handle heat from the media, the company has retained Charles Harder, the lawyer most famous for winning Hulk Hogan’s $31 million lawsuit against Gawker in 2016. In at least one case so far, Harder — who has become something of a boogeyman to publishers — sent a legal demand letter to Bloomberg when it published a story alleging the Internal Revenue Service had subpoenaed Kushner Companies’ business partners.

Meanwhile, Jared Kushner has his own legal team, headed by white-collar attorney Abbe Lowell, who also works for New Jersey Democratic Sen. Robert Menendez. In 2015, Menendez was indicted on corruption charges, which he later beat.

It’s not clear, however, who is spearheading the legal preparations for the family business.

“You do need somebody to coordinate all the defenses,” Levenson said. “It’s kind of a logistical nightmare in some ways, and it is very difficult.”

Josh Stein, a real estate attorney in New York, echoed that point. “The problem is when you get an investigation like this, you can’t just bring someone in and say, ‘respond to the investigation,’” he said.

“Before you let the investigators rummage around too much, you have to think about what it is that happened and what they’re looking for,” Stein added. “You don’t want to be blindsided. But you can’t easily delegate that to someone who wasn’t involved in the situation.”

One source close to the Kushners complained that the investigations have typically followed explosive news stories on the same topic, rather than originating from intelligence first gathered by law enforcement. The timing, at least, is true of the EB-5 and Deutsche Bank investigations, as well as an inquiry into the firm’s push to have tenants in Maryland arrested.

In New York City, it was also the case after the Associated Press published a story alleging Kushner Companies had lied to the Department of Buildings about whether there were rent-regulated tenants living in buildings where the company was doing construction work.

The DOB then announced that it would investigate the firm, and Council member Ritchie Torres launched his own inquiry — looking into claims that Kushner Companies misled the agency to allow the construction work to move forward without stricter government oversight.

Torres declined to comment on the ongoing investigation. But the subject matter quickly made its way up to the U.S. attorney’s office for the Eastern District of New York, which subpoenaed the firm for documents on how it handles rent-regulated tenants, according to the Wall Street Journal.

“Go into any building,” Charlie Kushner said. “You’re going to hear the same stuff. I’ve been in business doing the multifamily for about 40 years. There’s just a lot more tenants than there are landlords.”

The Kushner Companies founder dismissed the allegations, saying his firm simply failed to properly “check the boxes.” He said the DOB incident was not intentional and maintained that the investigations come with their own agendas.

“They could waste as much time and taxpayer money as they want, but it’s all politically motivated,” he said. “And we’re, thank God, big enough and strong enough to deal with it.”

—This story is the second part of a series that began with a sit-down interview with Charlie Kushner and Laurent Morali for TRD’s June cover story.