Trending

Milstein dynasty back in fray

<i>Under the radar for years, developer now at center of lawsuit and gearing up to launch sales at two condo towers</i>

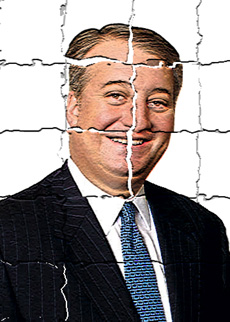

Howard Milstein is the head of Milstein Properties.

On a winter afternoon last month, sunshine streamed through the windows on the 33rd story of 30 Lincoln Plaza, illuminating the cleaning supplies and paint cans that occupy the high-ceilinged space.

Innocuous though it may seem, this out-of-the-way spot is at the center of a bitter dispute now raging between the building’s tenants and the developer, the Milstein real estate family.

In their quest to prevent the Milsteins from converting the rental building into condos, tenants have filed a lawsuit claiming that when 30 Lincoln Plaza was constructed three decades ago, the developer ignored city permits and added an illegal extra floor — the 33rd.

The building, they allege, is now seven feet too tall and five feet too wide, and exceeds the maximum floor area ratio.

The developer “had applied for a larger number of floors and the city turned him down,” said one tenant. “He said, ‘Screw them; I am going to build what I am going to build.'”

The suit, filed in December, also claims that billionaire Howard Milstein — the strong-willed current head of Milstein Properties — tried to cover up the alleged zoning violations by withholding information from the city and the state attorney general.

The family has until March 5 to respond to the suit.

Litigation is nothing new for the Milsteins. They are one of the city’s oldest and most successful real estate families, but also among the most controversial.

“The Milsteins are always pushing the envelope,” said Richard Farren, the attorney representing the tenants. “That’s what they did when they built 30 Lincoln Plaza, and it’s what they’re trying to do now that they’re converting the building.”

In recent years, however, the Milsteins have shunned the spotlight after a series of legal disputes caused a deep rift within the family in the early 2000s. During the real estate boom, they stayed mostly under the radar, making few acquisitions.

Many of their recent projects have been nonstarters: The family held a groundbreaking in 2002 at their 42nd Street site for a 35-story tower, but then sold the lot to SJP Properties two years later. In 2007, they announced plans for a residential building on a vacant 20,000-square-foot lot near Union Square, but the project never materialized. Even the conversion of massive 30 Lincoln Plaza, which has nearly 600 units, was largely kept quiet.

That’s about to change. In addition to the controversy surrounding 30 Lincoln Plaza, Milstein Properties this spring will launch sales of two condo towers in Battery Park City: Liberty Luxe and Liberty Green. The long-awaited two-building project, once thought to be off the rails, is the first new ground-up construction for the Milsteins in years.

Deep roots

Howard Milstein comes from a long line of shrewd negotiators.

His grandfather, Morris Milstein, started out scraping and refinishing wood floors after emigrating from Russia to the Bronx. In 1919, Morris founded Circle Floor Co., which eventually came to dominate the New York market, installing flooring at Rockefeller Center, LaGuardia and Kennedy airports and Madison Square Garden.

Morris’ two sons, Seymour and Paul, built on their father’s success. In the 1960s they began constructing apartment buildings, often in fringe locations that later became popular. In 1987, they built the 1,477-unit luxury rental Normandie Court at 95th Street and Third Avenue. In 1988, they erected Murray Hill’s 710-unit Windsor Court. They eventually amassed some 3 million square feet of office space and 8,000 apartments.

Along the way, they also bought companies like United Brands, the Starrett Housing Corporation and Emigrant Savings Bank.

Seymour and Paul were famous for their good cop/bad cop approach to real estate. Seymour was measured and diplomatic, while his younger brother was loud, domineering, and known for hard-nosed deal-making.

Both men, however, quickly gained a reputation for their epic battles with the city. In 1981, for example, they infuriated the Landmarks Preservation Commission by demolishing the Palm Court lounge of the legendary Biltmore Hotel.

After that, Paul in particular “was very unpopular with a lot of people,” said William Stern, who worked with the Milsteins in the ’80s as head of the state’s Urban Development Corporation.

“Paul was not comfortable with the extent of the government involvement in the real estate industry,” Stern said, noting that the developer wanted to “just build.”

The Milsteins battled for years for inclusion in the city’s 42nd Street Development Project, though the city repeatedly passed them over for other developers.

The brothers were millionaires many times over by the time Paul’s son Howard graduated summa cum laude from Cornell in 1973. Howard went on to Harvard Law School before turning his attention to the family business.

The brothers were millionaires many times over by the time Paul’s son Howard graduated summa cum laude from Cornell in 1973. Howard went on to Harvard Law School before turning his attention to the family business.

Though his younger brother, Edward, also works in the business, Howard established himself as Paul’s heir apparent early on. In 1978, Howard spearheaded the purchase of the Royal Manhattan Hotel on a then-seedy stretch of Eighth Avenue between 44th and 45th streets, reincarnating it as the Milford Plaza (known to many for its commercials employing the catchy song “Lullaby of Broadway”).

Another smart buy was Douglas Elliman & Company. In 1989, just two years after the stock market crashed, the Milsteins purchased the brokerage on the cheap from Edwin J. Gould and Lawrence O. McGauley, and installed Howard Milstein at the helm.

“Real estate in 1989 wasn’t a pretty thing in New York,” said Paul Purcell, the co-founder of Charles Rutenberg Realty in New York. The two worked closely in the 1990s, when Milstein owned Douglas Elliman (now Prudential Douglas Elliman) and Purcell was a top executive there. “It was a very scary period.”

Milstein hired new brokers and expanded the firm’s reach from the Upper East Side to the entire city. As the market recovered, Elliman reaped the benefits with a period of “exponential growth,” Purcell said.

In 1999, Milstein sold the company to Andrew Farkas’ Insignia Financial Group in two separate transactions for around $85 million. By contrast, Elliman’s current president and CEO, Dottie Herman, paid just under $72 million for it a few years later.

In many ways, Howard takes after his now-86-year-old father: He’s smart, savvy and “a very tough negotiator,” said one source who has worked with him. However, Howard, reared in Scarsdale, doesn’t have Paul’s humble beginnings.

At Elliman, Howard’s office was composed of a huge suite of rooms that included a gym and butler’s pantry. Milstein would hold court with a cigar “like the king of the universe,” Purcell recalled, noting that his boss could be charming, but also imperious and intimidating at times.

“He didn’t suffer fools easily,” Purcell said. “You had to know your stuff.”

Also like his father, who once referred to real estate as a “hobby,” Milstein devotes much of his attention to other pursuits (he is the former owner of the New York Islanders) and is known for having a problem with authority.

In the 1980s he founded his own cable company, Liberty Cable Co., after a disagreement with Time Warner over the cost of wiring the Milford Plaza. Though Milstein was proud of his challenge to Time Warner’s monopoly, he ran afoul of the state cable commission, the Federal Communications Commission and even the Motion Picture Association of America. He was fined for wiring his buildings illegally, misleading government agencies in filings and underpaying royalty fees.

In a statement in 1995, the state commission said the behavior was “a disrespect of a kind which this commission, frankly, has never previously encountered.”

Family feud

Paul and Seymour’s easy partnership didn’t repeat itself in the next generation.

Howard Milstein’s bombastic personality caused friction with Seymour’s more low-key son, Philip. When Paul became less active in the late 1990s after a heart surgery, the story goes, Howard tried to assert his dominance, resulting in a number of lawsuits that ultimately tore the family apart.

When Howard sold Douglas Elliman, he reportedly refused to give his cousin a share of the proceeds. Philip then sued, claiming Howard had improperly used Elliman funds in an unsuccessful bid to buy the Washington Redskins. For his part, Howard filed a suit seeking to oust Philip as chief executive of Emigrant Savings Bank.

By the time Seymour Milstein died in 2001 at the age of 80, it is said that the formerly inseparable Milstein brothers — who famously dined together daily at the Rainbow Room — were no longer speaking.

The fracas finally faded in 2003, with a settlement that essentially divided the company in two. Philip and his sister Connie founded their own company, Ogden Cap Properties, to manage their share of the family’s holdings, including Normandie Court, Windsor Court, One Lincoln Plaza, and the Dorchester Towers, as well as the Milford Plaza.

Paul’s family purchased Emigrant Savings Bank, installing Howard as president and CEO, and the family’s long-held (and increasingly valuable) empty lot at Eighth Avenue and 42nd Street.

Under the auspices of Milford Management and Milstein Properties, Howard and Edward manage four Milstein-developed properties in Battery Park City, Claridge House on 87th Street and the Highgate on the Upper East Side. Their holdings also include the 29-story Bank of America Plaza at 335 Madison Avenue (formerly the Biltmore Hotel.)

Since the blowup, both Milstein branches have kept a low profile. Howard Milstein did start buying property in Niagara Falls in 1998, and in 2003, he unveiled plans for a $12 million complex of stores, restaurants and entertainment attractions. But the project was never completed.

Downtown condos

For a time, it seemed like Howard’s Battery Park City condominiums would go the way of his Niagara Falls proposal.

In 2006, Milstein Properties was chosen to develop the last residential site in the waterfront community, which is owned by the Battery Park City Authority. The Milsteins announced plans for two new “green” condominiums there, with 421 apartments and a 50,000-square-foot community center at the base.

Completion was originally slated for 2008; instead, construction began that year, just days before changes to New York’s 421-a tax statute took effect, allowing the Milsteins to avoid including affordable housing at the site.

The project was one of many sites across the city where developers rushed to get foundations in the ground before the deadline, then halted or dramatically slowed construction as financing became scarce amid the economic crisis.

With work at the sites virtually halted, industry observers speculated that the project was dead, or that the towers would be transformed into rentals. But Milstein was one of several city developers who negotiated with construction unions to reduce labor costs, and by the spring of 2009, the project was moving quickly again.

Liberty Luxe, left, and Liberty Green, Milstein Properties’ new condos

Liberty Green is now topped out and should be ready for residents in September, according to a spokesperson for Milstein Properties. Liberty Luxe is slated for completion in January 2011.

Terry Lautin, a vice president at Prudential Douglas Elliman, noted that the Milsteins were lucky to avoid starting sales in the worst of the downturn. In Battery Park City in particular, she said, buyers have had trouble getting mortgages because the buildings have land-leases, giving pause to cautious lenders. Moreover, there have been problems in Milstein-built condos because of the family’s tendency to hold a large number of sponsor units.

Lautin noted that while the Milsteins developed a number of the early BPC buildings, they haven’t constructed anything there in years. “They haven’t built anything in the whole city for a long time. We’ll have to see how they do with these units,” she said.

Meanwhile, the rental-to-condo conversion at 30 Lincoln Plaza — located at 30 West 63rd Street — is now causing a bevy of unexpected headaches for Howard.

Drama at 30 Lincoln

With roughly 600 units, 30 Lincoln Plaza is one of several mammoth residential buildings constructed by Paul and Seymour Milstein near Lincoln Center in the ’60s and ’70s.

In 2006, Howard Milstein announced plans to convert the property to condos, but despite its huge size and high prices, there was no splashy marketing campaign.

That may have been because Milstein planned to sell only a few units and keep a large number of sponsor units. He currently owns more than 75 percent of the apartments in the building, according to the tenants’ lawsuit.

As the market soured in 2008, Milstein had trouble selling even the 15 percent of the units required for the offering plan to be declared effective by the AG’s office, the tenants’ lawsuit claims. To deal with those struggles, he unloaded around 80 units at deep discounts. Some 70 buyers have since closed on their units, a spokesperson for Milstein Properties told The Real Deal. The company declined to comment further on the litigation.

While the conversion plan was declared effective in December 2009, Vera Salnikova and a group of around 20 other tenants in the building filed a lawsuit in New York State Supreme Court against the sponsors and Attorney General Andrew Cuomo, demanding that Cuomo revoke the offering plan.

Salnikova — who had previously sued the sponsor in an attempt to remain in her apartment — and the other tenants claimed the “fire sale” was unfair because they’d been promised a 25 percent insider discount.

More controversial, however, is the suit’s claim that the offering plan is invalid because the Milsteins intentionally violated the building permits when they constructed the building, and then covered it up.

More controversial, however, is the suit’s claim that the offering plan is invalid because the Milsteins intentionally violated the building permits when they constructed the building, and then covered it up.

When the Milsteins began the approval process for 30 Lincoln Plaza in the 1970s, they had asked for a larger building — a 43-story tower with a floor area ratio, or FAR, of 21.6. Eventually they were approved for a 32-story — plus penthouse — mixed-use building with an FAR of 14.4.

The recent lawsuit claims that the building is substantially larger than that, with an FAR of around 15.6. It also alleges that the Milsteins falsely certified to the city that they had built the tower to the correct dimensions, and that during the conversion process some 30 years later, Howard Milstein misled the AG by saying there were no zoning violations at the site.

“These people have a track record of not being very truthful,” argued Farren, the tenants’ attorney.

Moreover, “the building [has] one too many floors,” the suit claims. While the 33rd floor (actually the 32nd, because there is no 13th floor) was described in the original plans as “mechanical space,” the sponsor actually intended to use it for additional apartments, the suit alleges. It points to the high ceilings and large windows as evidence.

A visit by The Real Deal last month confirmed that the 33rd floor — which now appears to be used primarily for storage — does indeed have large, residential-style windows and high ceilings.

The Milsteins have always contended they never intended to use it for apartments. “[It] was designed to be used as mechanical space and the space is today uninhabitable and not used for any other purpose,” wrote Paul Selver, an attorney for the sponsor, in a 1984 letter to the city.

However, the Department of Buildings issued a violation in 1984 stopping the sponsor from partitioning the space and putting in plumbing, indicating they planned to install apartments there, Farren said. The two parties were able to resolve the dispute, but only because the Milsteins hid the extent to which the building was overbuilt, the current suit says.

Selver’s letter conceded that “there is a difference of approximately five feet six inches” between what was built and what the Board of Standards and Appeals approved, but did not acknowledge the other zoning discrepancies alleged in the suit.

So how does a 30-year-old zoning violation — if it actually occurred — matter to a current-day conversion?

There is no statute of limitations on zoning violations, Farren said, so the city has the right to demand some kind of compensation, or even require that the extra space be demolished.

A spokesperson for the AG declined to comment, citing pending litigation, and the DOB did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The suit also claims that Howard Milstein “falsely certified” information in the offering plan, including the fact that there was no litigation in connection with the property, even after Salnikova’s 2008 suit was filed.

When The Real Deal first wrote about the suit last month, a Milstein spokesperson called the suit “complete nonsense from a tenant who has lost a number of lawsuits already.”

In Salnikova’s May 2008 suit against the sponsor, she claimed to be a rent-stabilized tenant, which would allow her to block a sale of her apartment if she decided against buying it. The judge rejected her request for an injunction, stating that Salnikova had signed a lease that “expressly declared that the apartment was no longer rent stabilized,” according to court documents.

Decision time

30 Lincoln Plaza is at the center of a lawsuit.

Even if 30 Lincoln Plaza is overbuilt, it’s possible that Seymour and Paul didn’t purposefully break the law. “The zoning laws are so complex that nobody knows what they should be doing,” Stern noted.

And while the Milsteins have their detractors, they also have avid supporters who point to their impressive record of successful projects, like the Milford Plaza.

Howard Milstein is “one of the smartest guys I’ve ever met,” said Purcell.

When asked about tales of Milstein’s storied arrogance, Purcell said: “He’s not a touchy-feely person. You can’t be loved by everyone when you’re that successful. He’s tough and he’s shrewd — that’s not a bad thing.”