Hochul plan for resi towers is tall order

Hochul plan for resi towers is tall order

Trending

Lawmakers reach sweeping housing deal with “good cause eviction,” new 421a

Landlords call boost for rent-stabilized units too small; tenants assail protections as too weak

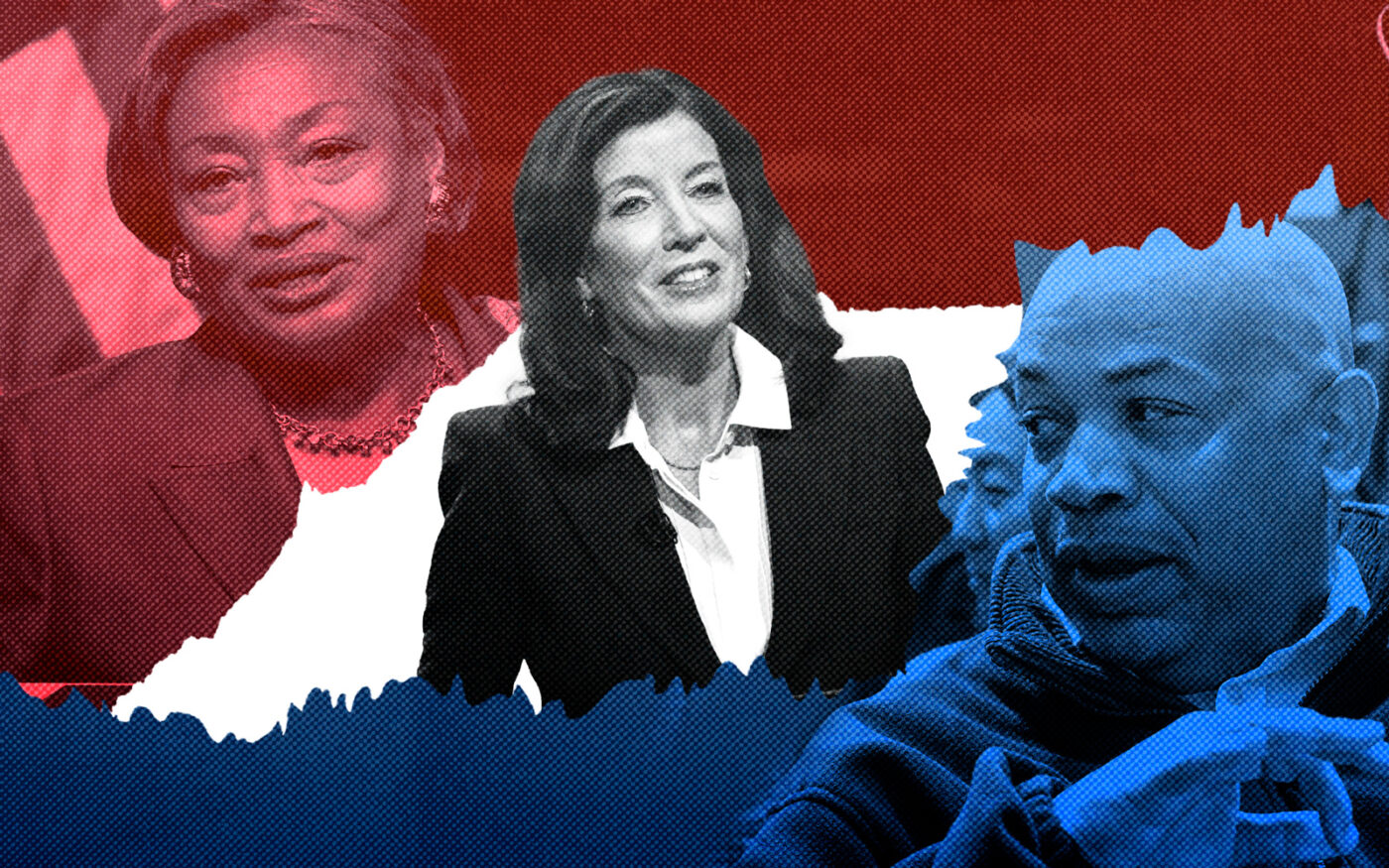

Fifteen months after Gov. Kathy Hochul proposed an aggressive plan to increase housing, she and state legislators have reached a deal.

It includes two of the most controversial real estate policies debated in recent years.

Hochul on Monday announced the “parameters of a conceptual agreement” that would revive a property tax break for rental projects in New York City and ramp up eviction protections. The pact incensed some real estate interests and made tenant advocates unhappy as soon as the details were leaked Friday afternoon.

The deal, as it stands, includes a version of “good cause eviction” and replaces the property tax break 421a. It also extends by six years the construction deadline for projects under the previous 421a program, which expired in 2022.

The good cause eviction terms appear to include significant concessions by proponents, who have tried for several years to enact a far-reaching version of the policy. During a press conference Monday afternoon, the governor did not refer to good cause by name, instead saying that tenant protections against “price gouging” would be included.

The original bill, proposed in 2019, would have given tenants the ability to challenge evictions that are the result of “unreasonable” rent increases, which it defined as more than 3 percent or 1.5 times the regional inflation rate, whichever is higher.

The proposal moving forward, based on news reports and reactions from tenant advocacy groups, appears to set that limit at 10 percent, or the consumer price index plus 5 percentage points, whichever is lower. It excludes higher-priced units — apartments where the rent is 245 percent of the fair market rent — and buildings where the owner’s portfolio includes 10 units or fewer.

New construction is exempt from good cause for 30 years, and the policy allows municipalities outside New York City to opt out, according to City & State.

In the weeks leading up to the deal, tenant advocates railed against the prospect of a watered-down good cause and urged lawmakers to walk away from any agreement that significantly diluted the measure.

But the legislature was determined not to let a second year pass without acting to boost housing supply. It also became clear that changes would need to be made to good cause to secure the governor’s support.

Landlord groups have vociferously opposed good cause, viewing it as universal rent control and an avenue to perpetual tenancy, and critics warned that it would curtail housing production and deter owners from renting out units — the opposite of Hochul’s goal. Proponents, however, called it essential to ensuring tenants who pay their rent can stay in their homes.

The new version of 421a, dubbed 485x, will require permanently affordable apartments for tenants at levels that are still being negotiated. The program will provide an up to 40-year property tax exemption.

A source familiar with negotiations said construction wage requirements for certain parts of the city will kick in for projects with more than 150 units, down from the old program’s threshold of 300. In those areas, pay will be the lesser of $65 or $72.45 per hour, or 60 to 65 percent of the prevailing wage — too high for REBNY’s liking.

In a statement, REBNY President Jim Whelan said the new program will “produce less housing than its predecessor.” He also said changes to a program that allows landlords to increase rents on stabilized apartments would “fail to reverse the declining quality of that housing stock.”

“And while there were several modifications to the original legislation, good cause eviction will still create significant new risks for owners, developers and funders,” he said.

The governor had left wage negotiations to the Real Estate Board of New York and the Building and Construction Trades Council, but the groups could not agree on terms. REBNY pitched a wage floor that would apply citywide, and then average wage requirements that varied depending on how expensive the neighborhood is.

The construction unions have criticized average wages as difficult to enforce. They were willing to accept a discount to prevailing wage, but wanted it applied citywide rather than in specific geographies.

One union, the laborers, had agreed with REBNY on a citywide wage floor that would by 2033 reach $45 per hour including benefits. That rate did not appeal to higher-paid unions, including the New York District Council of Carpenters, but is included in the budget deal, according to a representative for the laborers.

The governor’s press conference was light on details, but she said the budget would “eliminate density restrictions” in Manhattan, presumably referring to another housing policy that had stalled for many years: A proposal to lift the cap on New York City’s residential floor area ratio. This year, the conversation shifted and lawmakers ultimately got behind the proposal, though it was not immediately clear if additional restrictions will be attached. By lifting the cap entirely, which limits residential space to 12 times the size of a lot, the state would be giving the city the option to rezone areas to allow for greater residential density.

The Adams administration wants to create two new residential districts as part of its City of Yes for Housing Opportunity text amendment. The districts would permit construction of residential buildings 15 or 18 times larger than their lot size. Sites or neighborhoods rezoned to incorporate such districts would need to abide by affordability requirements under the city’s Mandatory Inclusionary Housing program.

Lifting the cap will pave the way for more office-to-residential conversions because many office buildings have a FAR above 12. The deal also includes a tax incentive for such projects, according to the governor.

In recent weeks, the fate of good cause eviction became tangled with proposals to increase the cap on improvements to rent-stabilized apartments.

Under the pre-2019 rent law, 1/40 of the cost of an apartment upgrade could be passed onto the tenant, and there was no limit to how much a landlord could spend. Rent increases were permanent.

The 2019 rent law capped improvement costs at $15,000 over a 15-year period, and limited the fraction that could be passed onto the tenant to 1/168 of the repair costs for smaller buildings and 1/180 for larger ones. That works out to $83 per month increases in buildings with more than 35 apartments, and $89 per month for smaller buildings. The increases are rolled back after the landlord’s costs are reimbursed.

Critics said the amounts were too low, given the cost of renovating units vacated after long tenancies. The new deal roughly doubles the allowed project cost and makes the associated rent increases permanent. It includes a tiered system for apartments, depending on building size, that would allow higher rent increases ranging from $166 to $347 per month.

Several proposals had been floated, including increasing the cap on renovation costs to $150,000, Democrat Brian Kavanagh, who chairs the Senate’s Committee on Housing, Construction and Community Development, said in an interview last week.

“Proposals like that are nonstarters, at least for me,” he said. “The goal is to make sure that we’re not talking about rent increases that are so large that they drive unaffordability.”

He added that while some rent-stabilized apartments are in severe disrepair, he feels that landlords are overstating how many units are vacant and need significant renovations. Estimates have ranged from 12,000 to 80,000.

Jay Martin, executive director of the landlord group Community Housing Improvement Program, called the tiered system for IAIs “convoluted” and “insufficient.” CHIP and another landlord group with which it is merging, the Rent Stabilization Association, called $30,000 not nearly enough to renovate apartments coming off long tenancies.

“This deal will not get any permanently vacant apartments back online. It does nothing to improve the financial stability of older rent-stabilized buildings providing the majority of affordable housing in New York City,” Martin said in a statement.

“Owners cannot possibly renovate old apartments for $30,000, are the tenants who could’ve moved into affordable apartments that still have no viable path to being restored,” said Aaron Sirulnick, chair of the RSA.

The groups note that 421a is a benefit for developers, not rent-stabilized landlords.

Said Martin, “This legislature and this governor have abandoned the renters and owners of rent-stabilized housing for billionaire developers and massive corporation owners.”

Read more

Hochul plan for resi towers is tall order

Hochul plan for resi towers is tall order

REBNY says its 421a proposal is a final offer

REBNY says its 421a proposal is a final offer

Adams wants to scrap parking mandates in new resi projects

Adams wants to scrap parking mandates in new resi projects